It’s the end of an era in music notation software. 35 years after its introduction as Coda Music Technologies’ Finale, the landmark scoring software is at the end of its life. Developer MakeMusic is offering a steeply discounted crossgrade to Steinberg’s Dorico, and says Dorico represents “the bright future of the music notation industry.”

MakeMusic is partnering directly with Steinberg to offer Dorico Pro as the new home for Finale users. The crossgrade is US$149 to the full Dorico Pro – versus a retail price of $579 – available now “for a limited time.” It’s also extended to Finale PrintMusic users. Basically, if you have any MakeMusic license in your account, I think this upgrade is a must-buy because it’s the lowest price ever for the top-of-the-line version of Dorico Pro.

Effective immediately, there will be no further updates to Finale, PrintMusic, Songwriter, Notepad – the whole line. Purchases and upgrades are frozen.

You can still use Finale on any machine where it’s already installed, but you won’t get updates, meaning OS upgrades could break your copy.

From August 2025, authorization and reauthorization will also end. (I expect that won’t go over well; it’d be nice to see them release a version without authorization requirements for compatibility at that point.)

They don’t mention file transfer in the press release, but now interchanging files between notation tools is far easier than it once was. Now is a good time to look at MusicXML (which MakeMusic helped champion).

The message from MakeMusic is clear: switch to Dorico. And the decision isn’t so surprising; Finale it seems just can’t keep up in the current market. From the press release:

Greg Dell’Era, President, MakeMusic and Alfred Music says: “Four decades is a very long time in the software industry. Technology stacks change, Mac and Windows operating systems evolve, and Finale’s millions of lines of code add up. This has made the delivery of incremental value for our customers exponentially harder over time. Today, Finale is no longer the future of the notation industry — a reality after 35 years, and I want to be candid about this. Instead of releasing new versions of Finale that would offer only marginal value to our users, we’ve made the decision to end its development. I am convinced Steinberg’s Dorico is the best home for our loyal Finale users, and is the bright future of the music notation industry.”

Steinberg has all the crossgrade info:

Frequently Asked Questions on Crossgrade

Dorico does seem the best choice, as it’s currently the most complete take on Finale’s (and later Sibelius’) vision. It’s not your only choice, but it’s gone the furthest in creating a complete system for laying out scores as automatically and visually as possible across a broad range of musical practices.

To put that in context, let’s go back to the 80s.

Finale history

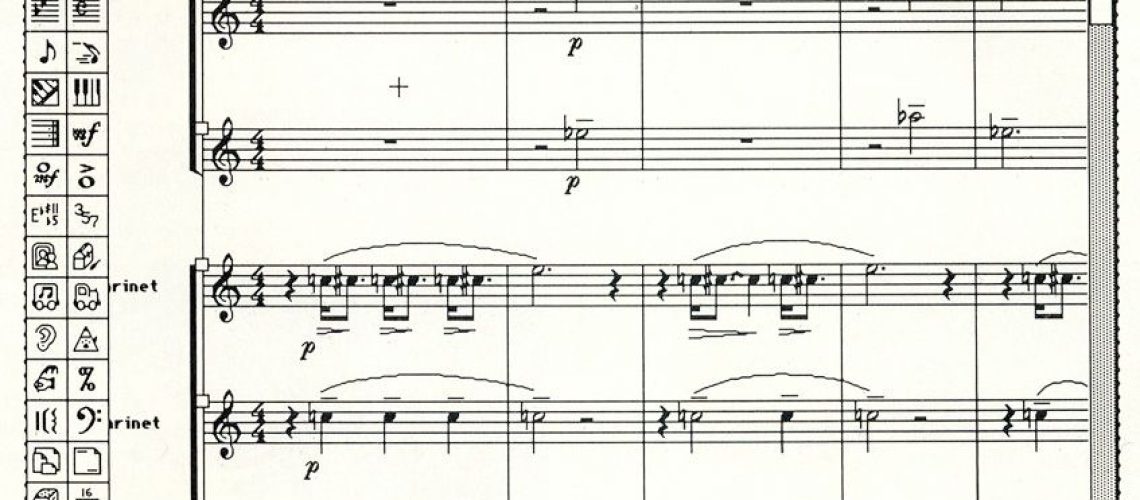

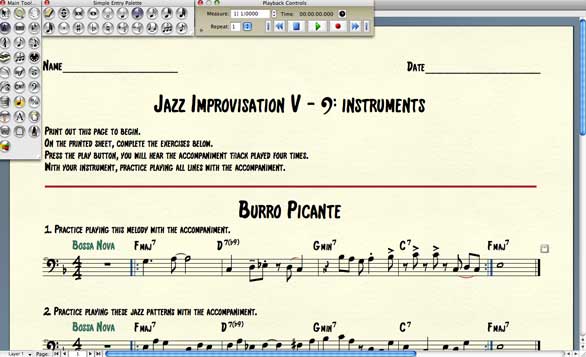

Finale arrived in 1988, the creation of developers Phil Farrand and John Borowicz. It was far from the only scoring tool of the era – what is now Apple Logic Pro began its life as Notator, for instance, and Farrand had even developed a simple Apple II notation tool (what evolved into Polywriter). But Finale was arguably the first product to fully marry a graphical interface and advanced automatic score tools. It had Photoshop-style tool palettes and could perform advanced spacing, beaming, and other notational tasks. And it did so with a degree of sophistication and advanced scoring output that set it apart from rivals like Passport Designs’ Encore.

Here’s a great review from December 1988 for Music Technology:

Coda Music Finale [mu:zines, my endless addiction]

(Or if you like, read my reviews for Macworld in 2011 and 2004.)

Get ready to see some familiar faces if you’ve been doing this for a while:

By the 1990s, Finale was the leading graphical tool for producing commercial scores, publishing, and TV and film work, a favorite of concert and Hollywood composers alike. I qualify “graphical” because many engravers still preferred tools that used manual processes more akin to how pre-digital engraving worked. (Leland Smith’s SCORE was a favorite well into the 90s – and if you thought Finale was arcane at times, SCORE ran in DOS without a graphical interface and was coded in FORTRAN.)

Great overview of the interface, even if it’s jarring hearing the Ableton Live 1.0 demo song (which will also make some of you feel like you’re on hold with the Berlin office in the early 2000s):

But then Finale had competition in the form of chief rival Sibelius. In the early 2000s, I was teaching in-service classes to K-12 instructors on using Sibelius, and I can say I had no qualms about savaging Finale’s more complex interface. To be fair, though, Sibelius and Finale each leapfrogged one another in features, with Finale continuously adding notational details that Sibelius often lacked, and introducing breakthrough functionality like advanced integration with Garritan Personal Orchestra.

It makes sense that Finale wouldn’t last forever. But there’s still something bittersweet about seeing an independent product laid to rest. And there’s just so much musical history bound up with this particular tool.

There’s also some arcane trivia to mention. An early (maybe the first?) version of the Finale manual was written by David Pogue, now known as one of the world’s leading tech journalists and a correspondent for CBS. The manual stint was predictive: he’s build his business on a series he dubbed “the Missing Manual.”

Phil Farrand when he wasn’t working on writing Finale had a second life as a Star Trek nitpicker – seriously – with Nitpicker’s Guides and Nitcentral, which poked holes in all the continuity issues in Trek, X-Files, and Star Wars. You can find those guides still floating around, plus some have evidently made it to Kindle.

But make that a third life, because Farrand went on to a successful career as a fiction and sci-fi author.

I’ll stop there, but I’m sensing a pattern. Someone starts their career in music notation software and Finale, then goes on to some almost comically nerdy career path later, and generally avoids writing scores again. Wait. I also fit this pattern. Fascinating.