Black-led, female-led, New York-based Willie Mae Rock Camp is providing inspiration to female and gender nonbinary musicians. Executive director LaFrae Sci talks to us about how it works – and it begins with breathing with a drum machine.

It’s dubbed “beat breathing,” and it’s inspired by IFOT – Indigenous Focusing-Oriented Therapy. LaFrae, who has entered the role at Willie Mae alongside a celebrated career as a drummer and musician, is certified in the practice. When I first encountered her, at Berklee’s Connect 2022 EDI (Electronic Digital Instrument) Summit, she leads the audience in the same practice that starts sessions with the students.

“My father is Yoruba,” she tells Connect EDI. “My mother is Yoruba-Nigerian, and my father is Afro-Cuban. And so the idea of music and spirituality and sound and transformation and freedom are very much things that I stand on.” With students currently aged 5-18, she sets an electronic instrument to about 85 bpm – the rehab TR-808 is a favorite. “The kids really love to breathe with the beat, she says.”

“You know the game Scattergories? We started playing Grattigories – you know, something that you’re grateful for,” she said at the Boston summit. She had students imagine sounds that they were grateful for. “One of the students — I might tear up, because this was so beautiful to me,” she says. “She said she’s grateful for the sound of the oven, clicking when the gaskets turned on in the morning when her abuela is making tortillas for breakfast. What is that sound for you? Feel it right now.”

Two years into an expansion into music technology and electronic instruments, what was founded as the Willie Mae Rock Camp now has 5-year-olds producing in Ableton Live and young students circuit bending and patching modular synths and live coding. That added STEM-informed skills just at the moment that students were falling behind in the pandemic. LaFrae Sci has a mind-bending deep background as a musician, spanning 30 years, major collaborations, and 38 countries. But she’s proving just as dedicated to supporting young people.

At the heart of this is the philosophy “mess around and find out.” Okay, originally that was “f*** around and find out,” but you get the idea – and it’s perfectly suited to tasks like experimenting with code or circuits. “That is an African-American vernacular English turn of phrase,” LaFrae is quick to clarify, just in case you’ve just been hearing it lately. “This is a phrase that many Black children heard from their mothers or grandmothers growing up for generations to make them act right,” she says.

One of the students said she’s grateful for the sound of the oven, clicking when the gaskets turned on in the morning when her abuela is making tortillas for breakfast.

Willie Mae’s students come from backgrounds that have been shut out of fields like music tech which are dominated by white men. “Most of the students were on the poverty line before the pandemic, and 98% are BIPOC, Black and brown girls, and gender expansive youth,” she says. Note the word “before” – the pandemic made things worse. Willie Mae, then, is a supportive space that has come in a moment of urgent need.

By the way, obviously the namesake of the program is the legendary Willie Mae “Big Mamma Thornton” (b. 1926), a singer, songwriter, and self-taught drummer. She’s the one who was a founding producer of rock, before anyone called it that. She recorded and performed “Hound Dog” and “Ball and Chain” well before Elvis and Janis Joplin did. But importantly, as the program notes, she also “transgressed gender and racial barriers — underrecognized in her time, her groundbreaking work paved the way for generations of female and gender nonbinary musicians to come.”

This is 1952 – and yeah, holds up better than the later recordings:

LaFrae spoke to CDM from Brooklyn – via Zoom, appropriately – to tell us more about how this process works, what these young folks are doing, and how the program works to keep the space safe and supportive.

CDM: It was moving to hear you talk about healing. What was this experience like, especially with the pandemic hitting New York and education?

LaFrae: Once I got into the classroom with the kids, there was so much trauma. Like 97 or 98% of our students were on the poverty line before COVID. So these kids are in home situations that are not conducive, necessarily, for a myriad of reasons, for learning.

And to be stuck there all day long. Imagine maybe sitting having to sit in the same room as your grandmother, watching her soap opera, while you’re trying to have headphones on and be in school, and then add to the fact that you’re 14. And you can’t go get your hair done. Yeah, when you don’t want to turn your camera on, you know what I mean? And then so I immediately had to turn to working on giving the students tools over Google Classroom. And so we started all of our students immediately learned about centering, breathing, checking in, visualization, and physical scanning. And all of these things have connections to the mind-body connection, that’s involved in the Yoruba tradition. And also IoT works with that. And even the deep listening also, you know, kinesthetic activation, it’s this whole thing.

So I brought all of that in. Also, the students learned how to raise their frequency, and, and curate their vibe. They understood that the same frequencies in the waves that make up everything, also feelings, thoughts, emotions. That was a great way to go back to music and through the blues tradition, which connects sound and intention to to heal, by sending it out, letting it go. That is the roots of the blues. I’d say that the blues is ancestors in alchemy.

And then I said this is not a short-term thing. I’ve always had my own spiritual, getting-myself-together practices that were outside of my musical work. So it was the solidification of bringing the healing, the music community empowerment, even closer into one — braided. So, yeah, we definitely meet the whole student. And we give voice for the student and and as an organization, we work with mental health professionals and refer students that we observed might be going through something.

So I saw you even have students doing circuit bending. How do they approach that?

They’re working with battery-operated toys, old toys, and taking them apart. And then using banana clips, to play with the circuitry and shift the sound that the toy makes. So that’s the basic level. And then on the more advanced level, we got young people taking those sounds, and collecting them to be used in a creative project. [sampling and rearranging]

Our actual scientific method – part of it is just mess around and find out.

And how do you work with software like Ableton Live? I’m especially curious, because I know that self-expression in software sometimes challenges even experienced adults.

Everything that we do, we scale. So there’s entry-level [tools]. Ableton is like a Swiss army knife — you can kind of do whatever. There’s so many ways to work with Ableton.

Usually, there’s been a tremendous amount of work and experimentation and ideas that then get come together in the DAW.

This cohort we have, like, it’s kind of crazy. We have [age] five to 16. So I was looking at this five-year-old, like, rocking Ableton, making a loop with her headphones, and I overheard her yell “this is my jam!” And I look, and there she is, like, on Ableton, making her loop, you know?

Ableton is this big, explainable lake that you can jump into that’s bottomless. But we just connect it. You’ve got older students that are working with more loop-based things using the other view of Ableton. And then, you know, other people that are kind of using Ableton as sort of the next step from GarageBand or Soundtrap. And understanding how to record, arm a track, and basic editing, and adding effects.

I was looking at this five-year-old, like, rocking Ableton, making a loop with her headphones, and I overheard her yell “this is my jam!”

How do you bring that “mess around and find out” attitude to something like a DAW – how do you help students find their own voice?

Because we also teach field recording, a lot of the young people are bringing recorded things and putting it into the DAW. Also, I encourage a genre-free zone.

It’s so easy, alike if you play a song for someone, and then they immediately say, “oh, that sounds like Brian Eno during that, like whatever period….” You know, people have been having to put music into boxes immediately. And teaching artists will do that, too — “that reminds me of” or “this sounds like.” So I train the teaching artists — don’t do that. Don’t tell them what you think it sounds like, because that’s your reference. And they do know about modern music and what’s going on in the world around them. But we don’t ask them to replicate that.

We had a share — a group, they decided to call themselves the LOL girls. They were ages six to nine. It was five of them; they collaborated, the whole cohort. And they broke up three times. And there had to be mediation. But their collaborative piece, like when I sent it to like Todd Barton, and people who really know, electronic music — they’re like, I have worked my whole career to sound this free. One of my friends said, they’ll never know how good they are right now.

And then they coded a visual of cats. And we played it and the parents were in the room and when the lights came up, the parents were like, you know, — it sounded like nothing you would ever hear on the radio for the rest of eternity. I had to explain to the parents that oftentimes genre-based music has the students emulating artists and they start, you know, jamming to the sound of their own oppression.

So we have this other way of being — just follow the sound. It’s all music. And that’s what I love about electronics, is because you can get really far outside of the Western and European classically oriented standards of correctness with tone and pitch and form. It’s what is music and what is noise and that whole thing — we keep it real open.

You could throw a baby in the water and it could swim. If you go into a room of kids who’ve never had any music training, and ask them to write a song, they can write a song. And they have a sense of narrative. We push collaboration. So basically, the LOL girls all added their parts together — from analog experimentation, and modular, and field recording. And then they just threw it all into Ableton, and then like, put effects on it. And then decided when it was time to step away from the canvas and put the paintbrush down. After three like Fleetwood Mac-level fights.

That’s amazing. And they’re also live coding – what are they using?

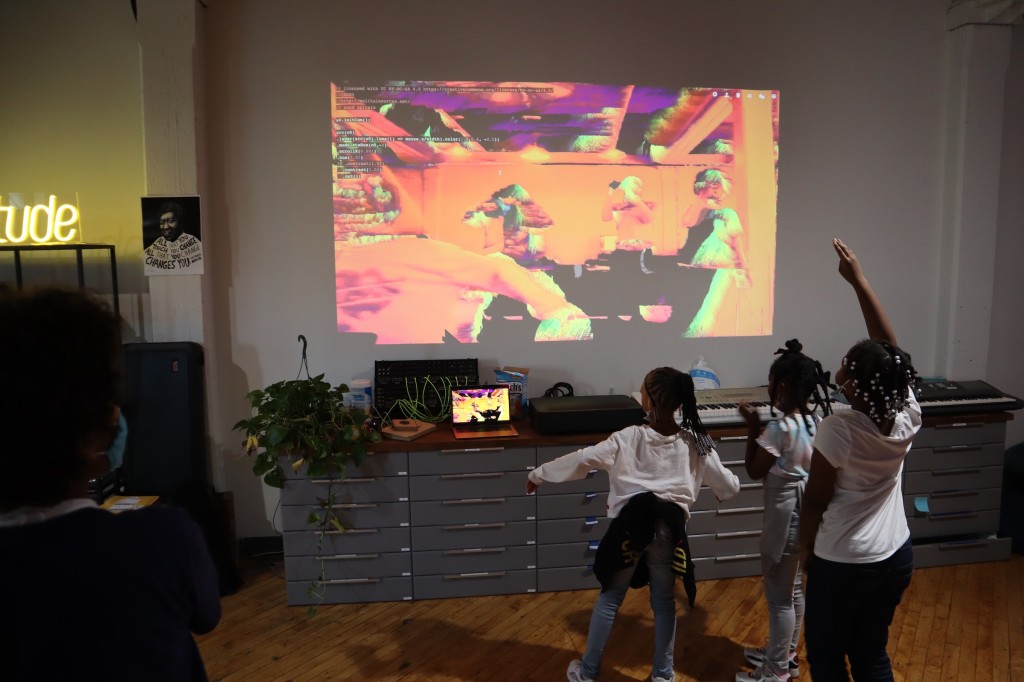

They’re working with Hydra. And I love Hydra. [visual live coding] Shout out to Olivia Jack.

We give them some basic variables to work with and understand. So they learn how to take an existing template that comes up in Hydra, and to mess around with the variables and change the color and the modulation and the oscillation. They understand how to bring visual elements from other places — like a picture of cats, or a video of themselves — into that situation. And then decode around that, and change the variables, and to create variables around that. They also know how to create variables activating the camera.

A couple of our teaching artists are actually real movers in the live code scene in New York City. So they bring that. I’m really into Orca, as well. [Ed.: Orca is a live coding procedural sequencer that uses single-letter operations and can send MIDI, OSC, and UDP – so can work with software like Ableton Live.] A lot of people would record into OBS [Studio] and then drop that into iMovie over like an image that maybe have them playing their instrument or whatever their narrative is for their final project.

What other projects are the students working with?

We have some solderless ones for the kids- the Thonk photon smasher. It’s cool. It’s a solderless kit, and you have an LED light and a sensor and it makes sound and so you run that into like an effects processor. And then you’ve got shaping sound.We also did Samantha Topley’s Giant Noisy Pom Poms. We actually found some other ways by using like banana clips and like squeeze balls. We’ve had some musical people come through and just put on a little concert. And we’ve had deep listening parties.

It’s great hearing the students talk about how supportive this space was. That’s not always the case in music making – for kids or adults. How do you make that happen? You’ve had experience as a gigging musician, I mean the music industry is very often not this kind of supportive space. Is there a way you bring that background to bear?

We normalize self-care and creative spaces. We just check in with the kid, if they need a break — you know, we’re not school. We’re inspiring, but we’re not shoving the information down their throats. So we meet them where they are.

And honestly, at this point, in my career, I don’t take a lot of gigs that are in the spaces that you described. It’s not my vibe, you know? So the bands that I tend to play with, a lot do have that awareness and move in spaces like healing. A lot of people are holding space for breathing, checking in.

One of the bands that I play in, the Burnt Sugar Arkestra, the founding director, Greg Tate, died. We pray and bring the spirit of Greg, to all shows. It’s just been a year that he’s been gone. So there’s a real intense spirituality in that particular band, as everyone has been engaged in different layers of grief.

How do you deal with those conflicts between students – like the Fleetwood Mac drama from the LOL girls? And is there anything you do to manage how people give one another feedback? Creativity I know can be a really vulnerable space, even for those of us who have been doing it a long time.

Generally, if you ever come to our space, most people sit, and they’re like — “s***, I don’t want to leave and I feel so calm here.” I’m like, yeah, we cultivate that. I don’t even think I think negative thoughts in this space. So there’s a way that we hold this space, with a real level of non-judgment — like, you rock, you rock, cool.

We definitely work on a level of communication and respect in the space without having rules — we call them our agreements. One of them is don’t yuck my yum. I mean, that’s a kid thing, but adults could go far with that, you know what I mean? We have such a way of getting the space set up for mostly positive kinds of reinforcement and communication. Most of the kids are able to frame their criticisms in such a way that it’s not like getting panned by a critic on your record.

We have agreements. One of them is don’t yuck my yum. Adults could go far with that.

How did you discover how to go about building the lesson materials? How do you keep it manageable?

I coached the Middle School Jazz Academy at Jazz at Lincoln Cente; it was a pilot program. And we would keep these crazy lesson plan documents — what was effective, what worked, what didn’t work. What I discovered in this process is that most kids didn’t learn more, or couldn’t retain more than three points. And then I was hired by the State Department to be the professional development facilitator for bands that were going out for their American Music Abroad program. What I also noticed in watching them teach was that these adults who were like academics or pros tried to pour everything that they’ve ever learned about the subject into their workshop. They would have like, 17 points and no takeaways. I realized that that metric of three things is really for adults, too.

What are you working now? What should people do if they want to support your work – where do you have needs?

I’ve just been, honestly, keeping this thing tuition-free. And building a new community of support posts. COVID is really challenging.

I’ve only had this position since 2020. And so we don’t quite have the data that a lot of larger grants want. We need individual donations and major donations of corporate support. So I have been just hustling my ass off.

We’re bringing in new kids every time. So right now we’re serving just shy of 600 girls, so it’ll be interesting to see how they grow with it. I’ll let you know.

Where to learn more:

Official site:

https://www.williemaerockcamp.org/

Learn more by signing up for the Willie Mae Rock Camp – they’ve now expanded across NYC, but there are plans for other cities, as well. The link is at the bottom of the main Willie Mae page.

Give to the program:

https://www.williemaerockcamp.org/donate

Follow on Instagram:

https://www.instagram.com/williemaerockcamp

You can follow LaFrae, as well:

https://www.instagram.com/fraefraedrum

There’s also a great story on NPR from this month:

Willie Mae Thornton was a foremother of rock. These kids carry her legacy forward

Major gratitude to La Frae, to Berklee College of Music EDI, and to Ableton (who are also a sponsor of Willie Mae Rock Camp).

All images courtesy Willie Mae Rock Camp. Used with permission.