Composer, producer, and percussionist debashis sinha delved into spiritual spaces of his ancestral India in a double-release from late last year. These projects interweave rhythm, mythology, decolonization, and artificial intelligence. We talk to Deb about his take on machine learning – uniquely humble and human just when we need it – and the significance of the sonic imagery on this album. He reflects on the process of making and meaning for these gorgeous releases.

In case you missed these, these two came out on our Establishment imprint at the end of the year.

In his use of artificial intelligence for Adeva_v000_04, debashis sinha’s music is uniquely programmatic – a nod to the well of musical storytelling he draws on in his frequent work for theater. While based on neural networks, the works are improvisational and spontaneous, as if simultaneously informed by Indian classical compositional gestures. This is machine learning with a culturally particular and contextual dataset, dreaming of traditional futures. Adeva’s record has its genesis a livestreamed rendition for Toronto Media Arts Centre.

In Brahmaputra, debashis sinha travels even deeper into mythology, in a release named for the holy Hindu river. It’s a record that itself evolved, starting in sounds for Toronto-based filmmaker Srinivas Krishna’s work “When the Gods Came Down to Earth.” There is a thematic thread, too, like a boat traversing a river – through the Bengali folk drum madal played in the first track, images of locations in Deb’s ancestral India, and other holy places in the Hindu pantheon with their associated tales. That opening percussion gesture is unfolded through all these spaces, mythical and modern.

Deb spoke to us this month via email from Toronto.

CDM: The Brahmaputra river brings us immediately to a place – nearly 4000 km of it, really. We spoke in your last release about these questions of roots, and how they relate to those of us born in North America. What did it mean to you to evoke this place?

debashis: Most of these places in the titles are referenced more as ideas and feelings of place, rather than as the places themselves. The way these mystical (and real) places operate in my mind and storytelling is not necessarily a response to geographical or environmental attributes — although they can be. These places I evoke for myself are frames or containers of feeling and imagined memory. Much of my work with sound that touches on my heritage operates in this way. In my practice, I’ve come to the point to trust the impulse enough and to allow it to unfold into many different gestures, like the songs on the Brahmaputra record.

Srinivas’ film of course was the genesis of this. How did you begin working with the film; how did that collaboration work?

Srinivas Krishna was a film director principally at the time of our collaboration (he’s doing lots in the VR space now). His extraordinary film installation [below] was to be exhibited at the Royal Ontario Museum in partnership with the Toronto International Film Festival in 2008, which was quite an extraordinary commitment of resources to something like this for the early 2000s. The conversations we are having now in 2023 about inclusion and diversity were hardly in the mainstream at that time. For the TIFF installation, Krishna wanted music, and since we had known each other peripherally for a while he came to me. We had a look at the film and had some conversations about the sound, and to be honest my recollection is that we were a little stumped. We both knew that we didn’t want something traditional or bound by culture in ways that were being imagined at the time.

He left me alone to dream. I had a traditional drum, a madal that I bought in Kolkata which I loved very much. (A madal is a double-headed Nepalese drum, but is used widely in the northeast of India and into Bengal). I remember sitting with it and improvising, and finding the figure that eventually drove the sound for the installation. I started with that figure, and followed it to the many places I explored. The soundtrack ended up being about 35 minutes long and had a very broad arc in the end. When I was done, Krishna came over and I sat him down in my studio to watch the whole thing. (The characters cut and crossfade; it’s not a linear edit, more like an installation.) I went to make tea, and when I heard it end I came up, and he gave me a big smile and said “I love it.” Fin.

I’m learning to listen to my body as I navigate my work.

What was the connection to your daughter for “Nilla”?

Honestly when improvising the melody line that we hear — eventually sung beautifully by Turkwaz’s Sophia Grigoriadis, a lifelong friend and incredible musician — the word nilla came to mind unbidden. It’s an anagram for my daughter’s name, though I didn’t realize it at the time. As that became clear, the song progressed with that in mind. I really am proud of that track — I feel like it captures some of what I feel of my love for her. And having Sophia sing on it was a no-brainer, as she has always been very close to my daughter as well.

It strikes me in Brahmaputra especially that there is this counterpoint of digitally-deconstructed rhythm and then human percussion, and that spawns some complexity in the interplay between the two. How did you go about composing these? Some of this is played live, and then how much forms in the post-production, back in DAW land?

It’s interesting – I’m learning to listen to my body as I navigate my work. Apart from the visceral, in-the-moment instincts at play during the performing and composition process, there’s often an underlying imperative that hums under longer periods of time. Going back to drum kit playing was part of that hum at the time.

In terms of the parts and the interplay in the percussion, there was a healthy amount of throwing things at the wall and seeing what sticks. Groove is such an ephemeral concept; it changes day to day for me in my own work. Many of the sounds that sound electronic are in fact played acoustically and processed very intensely. On “Thar” for example, the only programmed percussion is the kick drum figure at the beginning of the track – everything else is acoustic drums. I did a lot of the processing and sound design during tracking, and that informed the next part that I played.

I approached the drumming and the editing of those parts very much like I approach a lot of my sound design work, particularly for theatre: what’s missing in the story? What’s part of this world that I’m not hearing, or hearing too little/too much of? My work in theatre has taught me a lot, most important of which giving myself permission to approach each work as a story, to think of it as storytelling, that human and simple process. Under the sky, under stars, by a fire, in a pool of light.

As a drummer, I definitely have learned to pay attention to my body, to integrate it into my decisions and gestures. I don’t think I could do what I do if I didn’t.

Sure ye of bliss, of children, give us here to she who worships | o the beautiful sky (2022)

What’s missing in the story? What’s part of this world that I’m not hearing, or hearing too little/too much of? My work in theatre has taught me a lot.

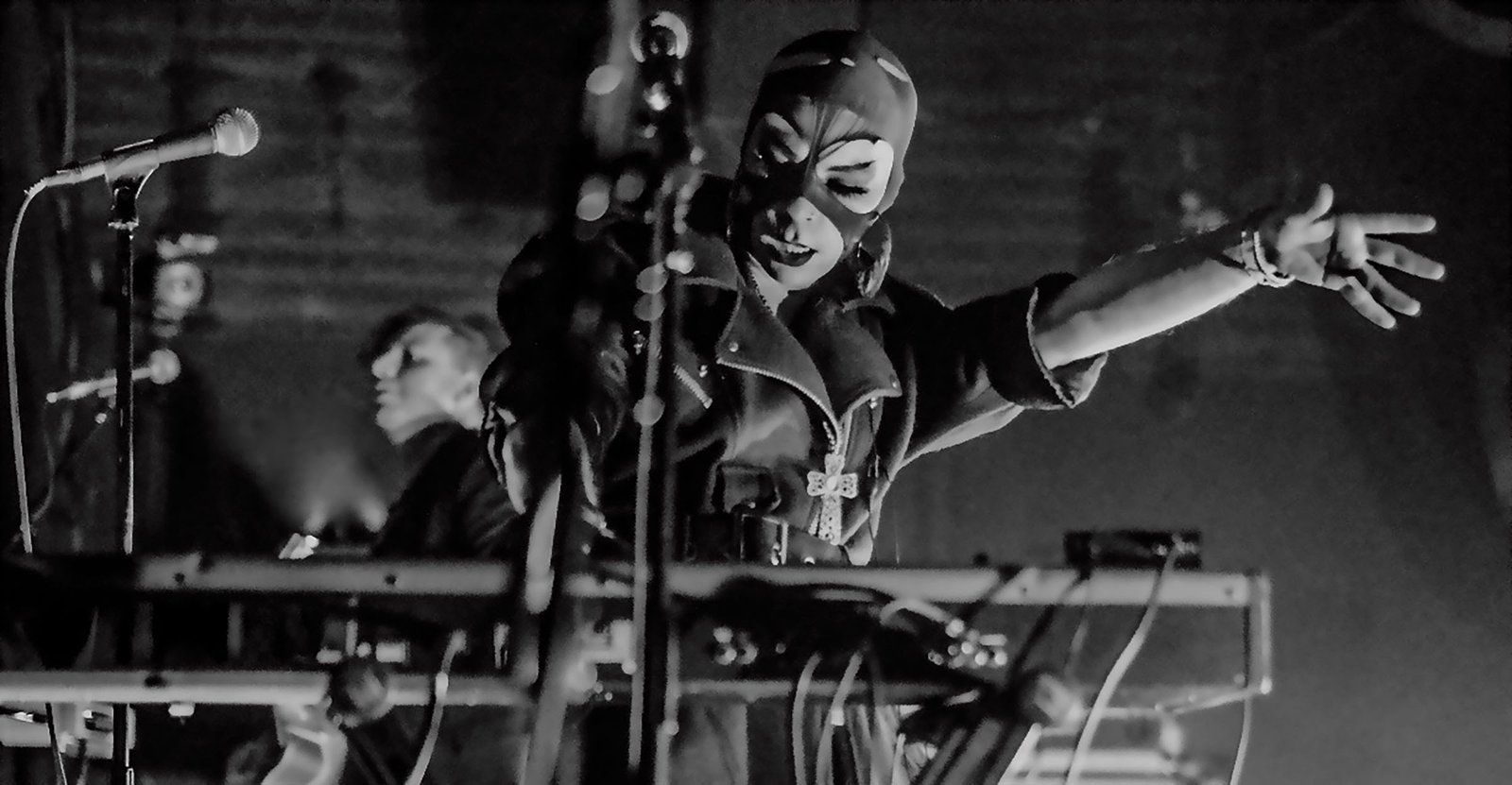

Text is important to Adeva_v000_04 in particular, and I know it may not be obvious to folks what’s happening there (which is itself evocative). Can you describe it? There are these beautiful images sonically, but also in the narrative and the titles. And then Suba also has this really particular, haunting style – how did that come about?

The text Suba reads is from a char-RNN – a neural network that looks at text at a character level, trained on a dataset and eventually predicting the next character in a sequence based on the training. Of course, text generation has made huge strides nowadays but when I generated this text, I tried actually interrupting the training after some epochs (cycles of training). I used an English translation of the Rig Veda, a fundamental Hindu text, to train the network, and I was intrigued by the outputs that resulted when I interrupted at various epochs – there was a sweet spot, definitely. What you hear on the record is lifted from the outputs of that RNN, with very little editing (but there is some).

I think the machine learning conversation elides the messiness of the process, what it leaves out when we try and quantize and quantify human experience. There are a lot of people wondering about this, trying to make spaces for viewpoints and world-building outside of market speak (https://manyfesto.ai/). I think it’s important to integrate an understanding of the failures of these networks into our understanding and use of them, especially as they become more and more integrated with applications where the integration not interrogated. I love what Anil Dash said some time ago on Twitter – that criticism is an expression of true techno-optimism, a belief that these tools can be better.

This framing makes a common error — being critical of extractive and exploitative technology *is* optimism. Saying that new tech shouldn’t happen at the expense of the vulnerable *is* an optimistic belief. Those who perpetuate the myth that criticism is anti-tech are the cynics. https://t.co/fVAMptyvB1

— @anildash@me.dm and anildash.com (@anildash) February 4, 2022

I like the failures that arise from the use of tools, and not just AI and machine learning tools. I’ve always been asking “what happens if I do this? What stories emerge?” Using prepared percussion or microphones in some kind of odd way reveal a lot of unexpected outcomes and material that in turn reveal also new ways to tell a story, for example. The text in Adeva is another expression of this process.

Sub and I have worked for many years together in early incarnations of Autorickshaw and other collaborations around Canada. I told her about the text and she was super game and curious. I asked her to be contemplative in her performance, to consider this text as a sacred text. She is an accomplished Carnatic and jazz singer, and her solid grounding in carnatic music (her father is mridangam vidwan Trichy Sankaran) and the religious connections that the text holds made her the perfect person to ask. She did an amazing job and I couldn’t be happier.

I think the machine learning conversation elides the messiness of the process, what it leaves out when we try and quantize and quantify human experience.

Improvisation is woven through both these records, and the connection to your practice as a percussion is so clear. How did you develop spontaneity in these pieces?

Improvisation is the only way I know how to do things, honestly. I do have a sound picture in my mind, sometimes, but I’m self-taught so I almost always fail in trying to reproduce what I hear in my mind, but that’s ok. I’ve come to understand those sounds as signifiers or signposts on the path to the final outcome, the final story.

As I’ve alluded to before, improvisation is a way for me to conjure the material I end up with, but improvisation is also part of the compositional process, the editing process, even the mixing process. I don’t have much of a mind or memory for processes of creating sound – I forget things as quickly as I discover them. I’m always in awe of people who can go “oh, this compressor will be useful here” – my Knuckleduster compatriot Robert Lippok is really good at that. Digital tools are a great way to keep track of your discoveries, but I came up working with them in a way that valued the discovery process rather than the replication process, I suppose. I’m always trying to figure out what the effects chain is for X when I’m working on Y.

Since Adeva_v000_04 was a livestream, how did you assemble that live performance?

The record started out as a livestream, in fact. I’ve had a long relationship with New Adventures in Sound Art – in fact, Darren and Nadene were responsible for opening up the world of sound for me. I sent them my first record “quell” back in the day, and they contacted me to ask me who the heck I was and how did I come to do what I was doing on that record. I went over to their space and they told me all about the world of sound art – I had no idea it was a thing. Anyway, Darren knew that I went to Japan to do the MUTEK JP AI Music Lab back in 2019 and invited me to do a livestream at the Toronto Media Arts Centre in cooperation with Charles Street Video, another venerable media arts institution here.

After the invitation, I realized I need to start thinking seriously about how I might use some of this content in a performative context, to experiment with the outputs of the various neural networks I was exploring at the time – it was quite a visceral and intimate way to build a story in real time (of course, the panic of a solid performance date had its own energy as well). I never really organize my Live sets beyond loosely organizing content – I keep meaning to at least colour code them, but…nope. Anyhow, in rehearsals for the live stream, certain ideas and sound worlds started to emerge, and after the concert I wanted to keep exploring these worlds in a more considered manner.

Let’s talk about what it means to make a culturally particular and contextual dataset. How did you select that dataset and training approach, with those values in mind?

Honestly, I’m not an engineer, so really I work in the Google Colab environment. I’m most drawn to notebooks that allow me to use the audio I create in certain ways – Adeva has a lot of the style transfer process, for example. As for culturally specific datasets, certainly, the tools are there to assemble a curated set that makes sense for the exploration one pursues, more so now than when I was working on Adeva (HEXORCISMOS is doing a great project with a number of us, implementing audio that a large cohort of artists have contributed into a RAVE environment for improvisation and composition – watch for a release soon). I spoke earlier here about messiness and failure, and these are the ideas that are interesting to me, and guide my explorations in this domain.

We are messy beings, full of contradiction. I think it’s worth celebrating. It’s something I want to prioritize in my work.

There’s a lot to unpack when we consider AI and art, and it’s not a simple issue. There are so many assumptions about knowledge, efficiency, scale, intelligence, etc., etc., that are all at play. To varying degrees there are many different ways to address the shortcomings and the structures implied in the field of AI and machine learning, but it’s imperative we widen our gaze, I think. We have to reject the impulse to “algorithmicize” our experience and the ways we organize our knowledge, true, but beyond that there is a necessity to make space for research and viewpoints like Kate Crawford’s Anatomy of an AI system, which considers the mineral resources and human labour required to get an Amazon Echo online.

We must incorporate an understanding of the complexity of the human and more-than-human intelligences that are involved in creating the body of knowledge that e.g. ChatGPT takes advantage of, and at the same time seek out the intelligences and experiences – and there are many – that are left out of that process. One space I’ve learned a lot from is Dreaming Beyond AI – a landing space for many communities adjacent to and often left out of the market-driven AI narrative.

We are messy beings, full of contradiction. I think it’s worth celebrating. It’s something I want to prioritize in my work.

So we did this AI Art Lab in what feels like another lifetime and universe for a host of reasons. What did you take from that experience; how did it inform the process here? There are a lot of folks in the acknowledgments; maybe you can say how they fit into this story?

2019 seems like many lifetimes ago, both in human and AI terms. I initially attended that AI Music Lab in Tokyo in order to orient myself – I knew that AI was coming down the pike, and honestly had no clue how artists were using it in their work. It was a fantastic workshop and helped me situate the tools in a larger and longer process of experimentation with technology that has always been present in sound and music. [See documentation of the Montreal edition of the same program we co-hosted.]

The people I acknowledge in the Adeva credits had a lot to do with this orientation, helping me settle in the somewhat overwhelming AI space to understand how my own practice and experience might meet it. A large part of that took place through insights and observations shared during the workshop, but also through longer conversations outside of it.

I think there’s a kind of overwhelming amount of information/power/energy in the AI conversation as it pertains to art-making. We are told in so many ways that we have to use a particular tool or network or workflow to make the most cutting edge or relevant or up-to-date AI art, and while it can be fun to use these tools and the results are sometimes very striking, we are not necessarily given room to consider what or how or why these tools might fit into the practice of making our own art. The conversations and credits I share in the Adeva record are a small gesture of thanks towards these people who’ve been so helpful in the putting together of the record, and there are countless other conversations in my life that help me keep focused on the stories I want to share.

From the Sankhya Stories series.

We are told that we have to use a particular tool or network or workflow to make the most cutting-edge AI art … and not necessarily given room to consider how these tools might fit into the practice of making our own art.

Ultimately these are both such evocative releases – do you intend to explore some of these worlds more in future work? Performances?

These sound worlds and workflows continue to be interesting to me. I’m working on a few different projects, and continuing to explore sound’s possibilities in and with AI. I’ve created a few different visual works sourced from (now) older neural networks that interrogate some of my own assumptions of what the colour and visual world of the traditional myths and expressions from my own culture might hold. Among other works, I’ve made a video series “Saṅkhyā Stories: Machine Learning Fables”, which is an idea I had and brought to November Paynter, the chief curator and associate director of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Toronto. MOCA commissioned a number of these fables for an exhibition in 2022.

I grew up on the Amar Chitra Katha comic book series, which made comics based on many different Hindu myths. When starting to work with CLIP (remember when that was new???) I had this idea that maybe I could make some moving image “comics” using these tools (“saṅkhyā” means “number” in Bengali). I wrote poems, and looked at some of the Rg Veda outputs I had in my archive, and found some image prompts that I tried out – these are the titles of each work. Many of the sounds were processed outputs from experiments using machine learning and AI on field recordings from Kolkata and my own electronic and percussion improvisations.

I think it’s important to mention here that the AI and machine learning workflows were only the start of the process of making these videos. On the one hand, that’s a result of the state of the tools at the time. But on the other hand — this is also something that doesn’t get spoken about much – there’s a lot of editing and human labour that goes into the making of many of these pieces, either in building the models or in working with the outputs to craft a final work. It’s an element of the discussion I allude to above with Kate Crawford’s Anatomy of AI project – that if we widen our gaze, we can perceive that there is so much going on behind the scenes that we need to be aware of or at least fold into our consciousness in using these tools.

I took some of my Toronto Metropolitan University students through the museum during the exhibit, and we had a great conversation about how much we neglect the process of work in creating art, that art is labour, with all the ramifications of how labour is expressed and constructed in the Capitaloscene. This holds true in the AI space as well.

I’m also keeping an eye on the communities that are doing some amazing work like Dreaming Beyond AI, the Decolonial AI Manyfesto and other communities that are trying to imagine a wider AI world. One amazing collection of essays I’m working my way through is “A Primer on AI from the Majority World: An Empirical Site and a Standpoint”. There’s so much research in this vein out there. I feel strongly it’s my responsibility to keep current with these initiatives as much as it is to gain fluency in new AI tools to create artistic work.

As for next steps – I’m not sure. I’m working on some new research projects with sound that are very much about conversation and how it allows a relational model of knowledge exchange. For sure this project will touch on data science and AI, given my wish list of people I’d like to talk to, ranging from (e.g.) people working internationally in global health to activists to actors.

Whatever ends up happening for me next with these worlds, I know it will have at its heart the act of storytelling.