Banning Confederate flags at country music concerts, dedicating nights to Black performers at Nashville’s Lower Broadway bars and instating a basic monthly stipend for Black artists in Nashville — these are some of the Black Music Action Coalition’s suggestions to better support Black talent in the primarily white country music community.

While country music festivals including Stagecoach and CMA Fest have specifically banned the use of Confederate flags at their festivals, BMAC urges other country music festivals and events to follow suit.

“It’s important that we understand that these symbols that country music has affiliated itself with, they are racist in origin and in current practice,” says BMAC board member Naima Cochrane, who has been a contributing writer to Billboard. “It’s not OK for me to sit in a room in 2022 and hear that a Black artist gets onstage and he sees more Confederate flags than American flags. Why should he as a creator have to be exposed to that? And why should a Black concertgoer have to be subjected to that?”

Cochrane and BMAC co-founder/co-chair Willie “Prophet” Stiggers shared their thoughts with Billboard following the release of BMAC’s 30-page, Cochrane-authored report “Three Chords and the Actual Truth: The Manufactured Myth of Country Music and White America.” The BMAC previewed snippets of the report on June 18 in Nashville and later provided Billboard with the full report and shared specific action steps to move forward.

Cochrane and Stiggers also urge artists who own bars in downtown Nashville to commit to a percentage of performances coming from Black performers.

“The Blake Sheltons and the Florida Georgia Lines have venues up and down Broadway where diversity policies can be implemented to ensure that Black musicians have the same opportunity to play,” Stiggers says.

The BMAC has been in talks with several music industry companies to support the creation of a $1,000 per month guaranteed basic income to give direct support for rising Black artists and young executives. Stiggers anticipates opening the application process in September, and launching a program in 2023.

“To be able to give a creative the opportunity to have some sort of economic support, but also wraparound services that include mentorship, resources and access, to help that person over a 12-month or a 16-month period to get the tools they need to create their business or release their music,” Stiggers says. “If Black country artists are having a hard time in Nashville, what about the R&B singer in Nashville? The rapper in Nashville, or the young girl that wants to be a music manager or be in marketing.”

The report traces a 100-year history of music industry practices and systems, from the use of the terms “hillbilly records” and “race records” to classify music by white performers and Black performers in the 1920s, to the use of Confederate flags at shows and the historical link between country music and the Republican party. The report noted key moments throughout country music’s history, touching on the careers of Black artists including DeFord Bailey, Charley Pride, Stoney Edwards, Linda Martell, Cleve Francis, Frankie Staton, Darius Rucker, Mickey Guyton and Jimmie Allen, as well as the crossover country successes of artists including Ray Charles and the Pointer Sisters. But it also detailed the lack of support Black artists have received from record labels and from country radio throughout the years.

Underrepresentation has been prevalent, it notes, with just one Black artist ever named CMA entertainer of the year (Pride in 1971) or ACM new artist of the year (Allen in 2021). Only three Black artists have been inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame since it launched in 1964: Pride, Bailey and Ray Charles.

As well, the report details the emergence of the Black Country Music Association in the 1990s, examines the decades-long span between the success of Pride and the rise of Rucker’s country career, and notes the response from Nashville’s artists and industry members as part of Blackout Tuesday in 2020 following the murder of George Floyd.

Last year, the BMAC issued its first report card on grading diversity within the music industry, and is set to release a second report card this summer. After the impact of the release of the 2021 report card, the BMAC wanted to focus on the country music industry.

“We wanted to do a deeper dive because the idea of accountability, holding our industry accountable to actively fighting systemic racism, the way so many companies pledged to do. We knew that Music Row would have to be part of that conversation,” Stiggers says.

“We knew we wanted to do a deeper dive and hold our industry accountable to actively fighting systemic racism,” Cochrane says. “We have an opportunity to speak to the country music audience, and to educate and elevate that fan base to issues around race.”

Cochrane began pulling together research in November, delving into the history and present-day story of Black artists in country music.

“We are aware, as I think all people are, that 100 years cannot be unraveled overnight,” Cochrane adds. “As with America, we are talking about ingrained systems and practices. It’s not as simple as saying, ‘You gotta hire some people or you gotta sign some people.’ You have to take more action.”

The report utilized previous statistics released regarding Black artists and country music, including a study from Dr. Jada Watson, titled “Redlining in Country Music,” which found that of the 411 artists signed to the three largest Nashville label groups (Sony Music Nashville, Universal Music Nashville, and Warner Music Nashville) from 2000-2020, 3.2% were BIPOC and 1% were Black. Over the course of 19 years, 11,484 songs were played by the top country radio stations, but those songs only represented 13 Black artists, with only three of those 13 songs being from Black female artists or groups.

The paper also highlighted the streaming’s ability to knock down color barriers. “Streaming is busting that door down,” Cochrane says. “My challenge is ‘Do you really want to present yourself as an equitable space?’ And that doesn’t mean only [for] Black people, that means other people of color. There has been a similar trajectory of Latino artists trying to make it in country music, making a little bit of headway and then getting pushed back out. There has long been a gender problem on Music Row, and an LGBTQIA+ issue. What’s happening now is these communities are forming and being collaborative with each other, supporting each other and going around those gatekeepers.”

BMAC has also focused on creating pipeline programs for college students and earlier this year, held a three-week music industry education accelerator program in partnership with Tennessee State University and Wasserman Music, with contributions by Nashville Music Equality and the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA). Twenty TSU students learned a curriculum that focused on music publishing, copyrights, labels, music marketing, touring and more.

“We assisted in building out the curriculum,” Stiggers says. “We brought in over 25 speakers. This was an elective course, and the students took it very seriously. The opportunities that are in front of them are tremendous.” He adds that there are plans to expand the program to up to five additional schools through next year.

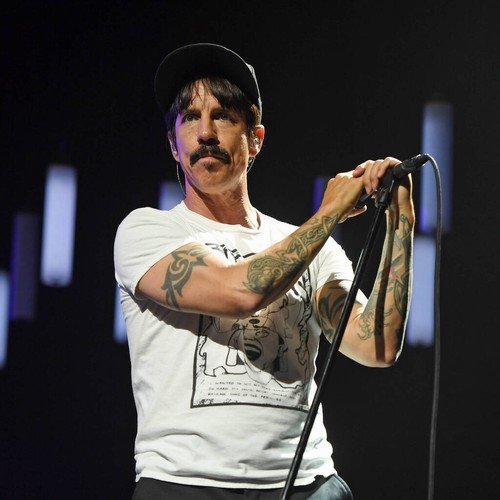

Naima Cochrane

Prophet

Courtesy of BMAC