Learn where to download audio loops, how to create a basic song idea, and how to expand a basic idea into a full song.

Affiliate Disclosure: This post may contain affiliate links to certain products. If you take action (i.e. subscribe, make a purchase) after clicking one of these links, Black Ghost Audio will earn a commission.

Once you’ve downloaded and installed a digital audio workstation on your computer, it can be pretty overwhelming trying to write your first song. The main issue is that you’re probably not too familiar with your DAW’s interface yet, and the other issue is that you likely don’t have a reliable workflow down that you can use to produce songs. Where do you even begin?

Taking an online course that teaches you how to use your DAW is definitely a good idea. You can follow along with a Pro Tools course, Ableton course, Logic course, or Studio One course. If you’re using a different DAW, I recommend checking out Udemy—this website has tons of DAW courses at affordable prices.

While a DAW course can be helpful, you don’t need to learn about every feature within your DAW before you write your first song. You can put together entire songs using audio loops, right now, using just a handful of the features built into your DAW.

Audio loops are audio recordings that are designed to be played back repeatedly. When you duplicate audio loops along the timeline of a project, they should play into one another seamlessly.

Learning how to use all the features in your DAW first, and then learning how to write songs, can be pretty dull and boring. In comparison, learning how to write songs first using the key features in your DAW, and then learning how to use the more advanced features afterward, is a much more fun experience, and it will motivate you to spend more time using your DAW—the result is that you’ll learn how to use your DAW quite quickly.

I do recommend learning at least a few of your DAW’s basic key commands before trying to tackle your first project because they’ll drastically speed up your workflow. At a minimum, you should look up the keyboard shortcuts to copy, paste, duplicate, and split audio clips in your DAW. For this tutorial, these are the only keyboard shortcuts you’ll need to know.

Your DAW’s user manual will contain more keyboard shortcuts, but there are keyboard overlay mats that you can get that have the keyboard shortcuts for certain DAWs printed on them.

Okay, so what does working with loops look like? Well, within your DAW, you can arrange audio loops along a timeline, moving the loops forward or backward in time. Layering loops together will create more complex, and potentially, more interesting arrangements. By repeating loops and adding variations to your arrangements, you can use loops to write entire songs.

Now that we’ve covered the basics, let’s take a look at where to find audio loops, and how to turn them into full songs.

1. Download Some Audio Loops

The first thing you need to do is get your hands on some audio loops. I put together a FREE sample pack you can download that includes loops that work together—no matter how you arrange them, they’re going to sound good when layered. To follow along with the rest of this tutorial, this sample pack is all you’ll need.

If you’re using Logic, you have access to quite an extensive library of Apple audio loops, and if you’re subscribed to PreSonus’s Sphere bundle, you have access to a bunch of audio loops as well.

Assuming you’re using a different DAW, there are a number of places you can download additional audio loops.

The number one place that a lot of producers download loops is a website called Splice. With this website, you pay a monthly subscription, and you’re provided with credits that you can use to download audio samples.

Traditional sample pack websites make you purchase entire sample packs to gain access to samples, but the cool thing about Splice is that you can audition the samples within different sample packs and only download the samples you want. This means that you won’t end up wasting credits on sounds that you’re never going to use.

Splice starts at $7.99/month, and you’re provided with 100 credits each month, but you can upgrade your plan even further if you need access to more credits.

Another popular sample website is called Loopmasters. They have their own credit-based system called Loopcloud, which provides you with up to 5 free sounds each day for free, with the option to upgrade to a paid plan for access to more samples. If you’d prefer to just outright pay for an entire sample pack, without subscribing, that’s also an option.

When you’re just starting out, I actually recommend you get one or two rather large sample packs, with a variety of content in them, just so that you have some material to work with. These sample packs will act as the foundation of your sample library, which you can add to later on.

Most sample packs are themed, so mixing together loops from a single sample pack should generally result in a song that sounds pretty cohesive from a sound-selection standpoint.

To create more interesting arrangements, you can mix samples from various sample packs together, but there’s no guarantee these sounds will work together. Sound selection plays a huge role in the final quality and clarity of your song, and over time, you’ll develop a sense for the types of sounds that work together, and those that don’t.

I’ve included links down below to some really comprehensive sample packs that include drums, synths, pads, FX, and much more. To kick off your sample library, these packs are a great place to start.

Once you’ve downloaded a few sample packs, make sure you create a folder somewhere on your computer and label it “Sample Packs.” If you don’t do this, you’re going to end up with sample packs scattered all around your hard drive, making it really hard to locate them within your DAW.

2. Create a Basic Song Idea

Alright, let’s crack open a DAW and load some audio loops. I’m using Ableton here, but the general workflow I’m about to demonstrate is the same regardless of which DAW you’re using.

The first step is to change the tempo of your project. A song’s tempo refers to its speed, or put simply, the rate at which you bob your head when listening to the song. A slower tempo is going to result in a slower head bob, while a faster tempo is going to result in a faster head bob.

All the samples in the free sample pack I gave you were created to be played at a tempo of 150. This means that if you listen to one of these audio loops on repeat for one whole minute, you’ll bob your head 150 times. The more technical term for one of these head bobs is a “beat.”

To accommodate my sample pack in Ableton, I’m going to change the tempo to 150 by clicking on the current tempo, which is 120, and then typing in 150, and pressing [Enter] on my keyboard. Now, when I import my loops, they should all line up with the grid along the timeline.

To load one of my loops into Ableton, I can just drag and drop it onto Ableton’s timeline, directly from the folder it’s in on my computer, or by finding the folder in Ableton’s Browser, and dragging the samples onto the timeline from there.

Layer all of the loops included in the free sample pack on top of one another along the timeline in your DAW. When you engage playback, you’ll hear that you’ve create a basic song idea that you can now stretch out and arrange into a full song.

3. Developing Your Loop into a Full Song

If you wanted, you could duplicate this loop a number times to the two or three minute mark and call it a day, but the song would sound extremely repetitive. To avoid repetition, you should provide your song with some structure, by breaking it down into different sections.

There’s no hard and fast song structure formula you need to use when writing a song, but you do need to structure it somehow to ensure that the song’s energy develops and progresses over time.

Traditionally, a song will have an intro, a few verses, some choruses, maybe a bridge where the vibe changes a little bit, and then an outro.

For EDM tracks, there’s typically an intro, a few breakdowns, generally two buildups and two drops, along with an outro.

Again, you don’t need to use these song structure formulas, but they’re popular for a reason, and it’s because they work—what I mean by this is that they help to drive a song forward, while providing enough repetition to make a song sound “catchy.”

What I like to do is find songs that I’m inspired by, and borrow their song structure. This doesn’t mean my music is going to sound like a duplicate of the song I’m borrowing the structure from, it just helps me develop basic loops into more interesting arrangements. Using the exact same song structure for every song I write can become redundant, so I tend to pull song structures from different songs as often as I can.

First, I’m going to import a hip-hop track into my DAW that’s at 150 bpm, or beats per minute.

You can find the BPM, or tempo, of songs in a number of different ways. The easiest way is to just Google “Song Name tempo.” The tempo of the song should pop up and you’re good to go. For most popular songs, this method should work.

If you can’t find the tempo of a song online, you can use a BPM analyzer. There are various BPM analyzers online that you can use for free. Get Song BPM is one example of an online BPM analyzer and it gets the job done.

The way that I like to analyze the BPM of songs is through an application called Mixed in Key. I can import multiple songs into Mixed in Key and it provides me with the BPM of all of them; it also adds tempo metadata to the songs, which will appear in iTunes. If you wanted to analyze your entire iTunes library, you could do that. Another benefit of this software is that it tells you which key a song is in, which is something we’ll explore in a minute.

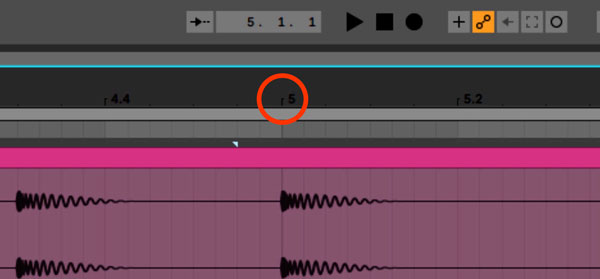

I’m going to zoom into the timeline and make sure that the first beat of the song lines up with the first beat of the fifth bar in my session.

In 4/4 time, which is a concept I’ll get into in the next video in this playlist, one bar on the timeline consists of four beats, so I’ve left 16 beats of silence before the song starts.

The reason I’m not lining up the song right at the beginning of the project is because I want to leave myself some room, just in case I want to add an effect like a riser or some dialogue leading into my arrangement.

Lining up a song with the timeline in your project is much easier when using a song that starts off with an impact, like a kick, because you can visually see where the first beat is. The rest of the defined peaks in the audio file’s waveform, which are known as transients, should line up with the timeline of your project as well. If they don’t, and they look way off, you may have identified the song’s tempo incorrectly, or set your project tempo incorrectly.

Now, I’m going to listen through the song, and use Ableton’s markers to label where all the sections are. In some cases, you can see where sections start based on the level of the song’s waveform. Once I’ve done this, I can mute the song, and use these markers as reference points to convert my basic arrangement into an entire track.

I’ll start by moving my arrangement over so that it starts at the same point in time as my reference song. Then, I’ll duplicate my arrangement so that it fills in each section I’ve created.

What I’m going to do now is start removing loops from sections that typically have less energy than the choruses. I can take a fair number of loops out of the intro, the interlude, and the outro, but I still want to keep the groove going during the verses, so I’m not going to take away too much content there.

Before you even listen to this, you can see that the song has a visual structure. Upon play back, you’ll hear that each section contains a shift in energy, which is exactly what you want.

If you need a little help determining which loops to remove in certain sections, you can use your reference song as a guide. If there’s no kick and snare in the intro of your reference, consider removing the kick and snare in your song as well.

To make the transitions between sections a bit more fluid, you can add FX like risers and down sweeps. On top of this, you’re now free to beef up certain sections of your song with additional loops if you want, or make revisions to the loops you previously got rid of.

For example, you may want to add some pads to your bridge, or add an additional instrumental layer to the choruses.

Instead of completely removing or replacing loops, you can add variation by shortening and duplicating them, as well as reversing them.

4. Match the Tempo and Key of Loops

Websites like Splice allow you to search for loops based on their tempo, which can help you find loops that match the tempo of your project. However, you don’t necessarily need to use loops that match the tempo of your project because almost every DAW includes a warp feature that allows you to apply time compression and expansion to audio files.

For example, if you want to use a loop that has a tempo of 130 BPM, you can apply time compression to it, to speed it up to 150 BPM.

In Ableton, it’s really easy to do this. Double-click on the audio file within Ableton’s Arrangement view, and then click on the “Warp” button in Ableton’s Clip View section. Within the segment BPM section, type in the native tempo of the audio file, and then hit [Enter]. The audio clip will adjust to the tempo of your project.

If you’re using a different DAW, it should contain a similar feature that allows you to warp the timing of audio loops.

You may find that certain loops don’t work together, even if they’re both at the same tempo. One reason they may not work is because the rhythm of each loop clashes, and creates a rhythmic pattern that’s hard to follow along to.

Another reason two loops may not work together is because they’re each within a different key. What this means is that the notes used within each loop create dissonance, or an unpleasant feeling, when layered together.

In the next video in this playlist, I’m going to provide you with all the basic music theory you need to know as a music producer, but for now, you can cheat the system by taking a look at the key of samples, which is often indicated beside the name of the sample using a letter, potentially a flat or sharp symbol, and potentially an “m,” or the word “minor,” to indicate that the sample is in a minor key.

For example, a sample in the key of F# minor is going to likely layer well with another sample in the key of F# minor. However, an F# minor sample isn’t necessarily going to work with an F# major sample, G minor sample, or D# minor sample.

Here’s a list of some of the common keys you’ll run into, which you can use as a reference.

I’ll explain how this all works in the next video, but if you want to start working with loops right away, all you need to worry about is making sure that the key of all your samples match. Pick a key, like F#m, and then make sure all the samples you download are also within the key of F#m. On Splice, you can filter samples by their key, so it’s really easy to find what you’re looking for.

It’s also possible to modify the key of samples, but to do this, you need to know a little bit more about music theory. In the video coming up next, I’m going to show you how to start writing your own melodies and chord progressions, as well as tune samples to the key of your song.

Once you learn about the basics of music theory, you’ll be able to start working with virtual instruments and synths, and be able to customize your arrangements further.

5. Export Your Song

The last step in creating your first song is exporting it so that you can listen to it in iTunes and upload it to Soundcloud or other streaming services. There will either be an Export or Bounce option within your DAW’s file menu that allows you to export your song as a single audio file.

Before exporting your song, make sure that you’ve selected a range along the timeline that you want to bounce. In Ableton you do this using the loop brackets.

You can export your song as is, but the resulting audio file is going to be pretty quiet. Each track in your session runs into something known as a master bus, sometimes referred to as a stereo bus. As you can see here, the transients of my project aren’t reaching the maximum value.

I could turn up the of my master bus, but this might cause the peaks to exceed the 0 dB limit of my DAW and result in a form of waveform distortion called clipping. To avoid this distortion, while maximizing the loudness of your track, you need to use a device known as a limiter.

A limiter reduces the dynamic range of sounds, preventing loud sounds from clipping, while still increasing loudness. I’m going to talk about limiters more in-depth in the mastering section of this playlist, so you aren’t expected to fully understand how they work quite yet.

To make your song louder before exporting it, look for an audio effect called a limiter found within your DAW, and apply it to the master bus of your project. Open the limiter, and reduce the threshold level until you see between 2-3 dB of gain reduction being applied.

You’ll hear the song start to become louder, but the tradeoff is that it will become less punchy and impactful as well. To some degree, this is okay, just don’t push it too hard. If the limiter starts to cause distortion, just lay off the effect a bit.

Additionally, you should set the limiter’s ceiling to -1 dB. This is going to leave 1 dB of headroom, which will preserve audio quality and prevent distortion from occurring during the process of transcoding when you upload your song to streaming services.

The export settings you should use depend on a few factors, such as destination format, but using a sample rate of 44100 and a bit depth of 24 will work for now. You should also make that you apply dither when exporting.

Once your song renders, you’ve successfully just produced your first full song. Congratulations. It should sound at least somewhat comparable, in terms of loudness, to other songs in your iTunes library. From here on out, everything I’m going to teach you in this video series will help you improve the quality of the songs that you write.

We’ll be taking a look at music theory, building a budget-friendly home recording studio, mixing your songs, mastering your songs, as well as getting your songs onto music streaming services like Spotify using a music distributor.

In the next article in this series, I’m going to provide you with all the basic music theory you need as a music producer.

Subscribe to the Black Ghost Audio mailing list to get notified when the follow-up article gets published, as well as when we run music production plugin and hardware giveaways.