LANDR’s machine learning-powered mastering service is now more than a simple web tool. The quality of the results has matured over years of development, and you can opt for a plug-in version with a complete set of tweakable controls. So, is the current offering worth considering, even if you know what you’re doing with mastering tools?

There’s a sale on all LANDR products through January 2, so a review is timely. Adding LANDR’s processing capabilities into a plug-in, where you can use it in your existing workflow in a DAW / editor / whatnot, is likely to attract interest in a way the Web service didn’t. And just as importantly, LANDR works better than it did at launch.

Spoiler – and greetings to any mastering engineers reading this – I think, ultimately, this is not about replacing an actual engineer with AI-powered automation. (Sounds icky.) But it makes sense that mastering would be an area of audio where machine learning is more relevant than most. The basic idea of taking an input and modifying it to an output based on a large set of similar inputs is a pretty good description of how many of these models are designed to work from a data science perspective.

What really matters: does it work, and are you likely to use this tool to replace others or complement them?

LANDR, evolved, as plug-in

Over ten years ago, when LANDR was just getting started, I got early access to the first version of the company’s “AI” machine learning-trained mastering. And I’ll be honest – I didn’t like the results at all. LANDR deserves credit for going all in on AI early; while other tools have added algorithmic analysis and automatic settings, LANDR was the one that bet the whole tool on AI. But that first version had only crude controls for setting results to taste, and the black-box results just tended to squash the sound. Sure, it sounded louder, but not with any particular regard for the source material. Upload more variety of tracks, and those results got even less satisfying or more erratic. I tried it on a couple of tracks, but ultimately lost interest – it wasn’t noticeably more useful than just selecting a preset from a maximizer or limiter and and EQ.

That’s changed a lot in a few years. And that’s not just because AI technology has “magically” improved. It’s clear LANDR did a whole lot of work, both in incorporating a larger data set and in listening to feedback from users and mastering engineers.

So, forget at least some of what you might think you know about LANDR, especially now that the LANDR Mastering Plugin is available. You’re not required to buy a subscription; the new LANDR plug-in can be bought as a permanent license with a one-time fee. (There are other options, too, but more on that below.) You don’t have to be online. The plug-in uses an Internet connection to validate the license, but actual mastering can all occur offline – your music isn’t uploaded to the cloud, and you can do your mastering locally. (I tested some tracks with my computer’s Internet connection disabled.) And you have a decent amount of control over the results – it’s still designed for automatic operation, but LANDR has gradually added more controls. You can get a range of results, which means you still have something to do with your ears and taste.

What LANDR is and who it’s for

LANDR uses machine learning based on a training set developed with paid mastering engineers. They’re not training the tool on what you upload to the Web service – which is good because, apart from being wildly unethical and destructive, it would likely yield terrible results. LANDR’s results sound as advertised – it gives you results that are similar to what a first-pass might be like from a mastering engineer. If it incorporated a bunch of user data, you’d get something that approximates the results of what an average producer asks for. (I’d imagine everything would come out sounding like EDM cranked just into the red.) You just don’t want an averaged-out mishmash of what everyone is doing; that’s not useful or desirable – and may quickly become a problem with AI production services, but that’s another story.

LANDR’s results sound as advertised – it gives you results that are similar to what a first-pass might be like from a mastering engineer.

No, the idea here is that LANDR has spent a decade or so training their engine with paid engineers who are explicitly told how their work will be used, the company says. They’ve recently unveiled a new engine called Synapse, so those results have recently evolved. I’m unclear on exactly what was rolled out when – as I said, I tuned out – but if you haven’t tried this recently, it’s worth giving the free Web results a try. And they’ve been testing on the other side, too, with the tool in use with serious producers and engineers. (The company likes to tout Disney, Warner Bros, and Def Jam, along with some unnamed Grammy Award-winning engineers, for what it’s worth.)

The company is a little cagey about how they perform the training or precisely how the mastering works. That’s now par for the course with commercial consumer products, in contrast to the AI research field, where publicly sharing results is expected. But LANDR does say that the software is making an array of adjustments, including multi-band compression, equalization, stereo field enhancement, limiting, and harmonic saturation.

It’s not far off the way auto-enhance tools in image editors have worked for years, in other words, but using machine learning to map input rather than heuristics. That way, LANDR is more likely to adapt its automatic parameter tweaks accurately to the source material.

Unlike big data “AI” offerings in imaging and text, this tool isn’t just stealing the work we all did on the internet and pooping out generic (or even inaccurate) results. It’s trained by mastering engineers who were told what they were doing and paid.

This obvious target here would be a casual bedroom producer, but if you really don’t know what you’re doing, you can just hire a mastering engineer for your first EP for roughly the same cost. Instead, LANDR claims these tools are intended to stand toe-to-toe with traditional mastering services and studio production. That makes some sense for anyone under tight deadlines. Say you’re working with a vocalist or client who wants a bunch of what-if scenarios and wants it yesterday. Sure, you might wish for the finished product to go through a mastering engineer or use your usual software and/or hardware arsenal. But if they need 20 different versions, or you have a few minutes to upload a live set, you might not want to answer the question, “Why isn’t this louder?” You get the picture.

Plug-in controls and usage

The plugin is available for macOS 10.14+ / Windows 10+ (64 bit) and AAX, VST3, AU. I was a bit disappointed not to find a manual – they’re really leaning into the idea of you just using this without much explanation. (The online help is beyond barebones.) That’s nice from a discoverability standpoint, but given the price, I’d like to see more configuration and documentation. Hey, I’m available for technical writing.

Workflow with the plug-in will be pretty familiar, though, and it does walk you through the process. Drop this on a master track (or stem/group, as I sometimes did, instructions be damned), and then cue up a few seconds of the loudest portion of the track. You’ll get a display (and pretty animation) saying LANDR is performing analysis, and after a few seconds, you’ll hear the results, and the full plug-in interface will appear so you can adjust to taste.

The analysis dialog notes that it’s “listening” and then as the analysis continues, demonstrates what parameters that means: frequency balance, dynamic range, stereo image, and genre. It’s the last one that’s AI-dependent because the “micro-genre” analysis LANDR touts needs that machine learning training set in order to work. Machine learning is good at this kind of large-scale automated pattern recognition; that’s really what it was designed to do. (It’s the rough equivalent of finding a reference track for mastering.) You can reset this analysis by hitting the Master button again – useful if you want to attempt a re-analysis at a different point in the track. Your parameter adjustments remain, too.

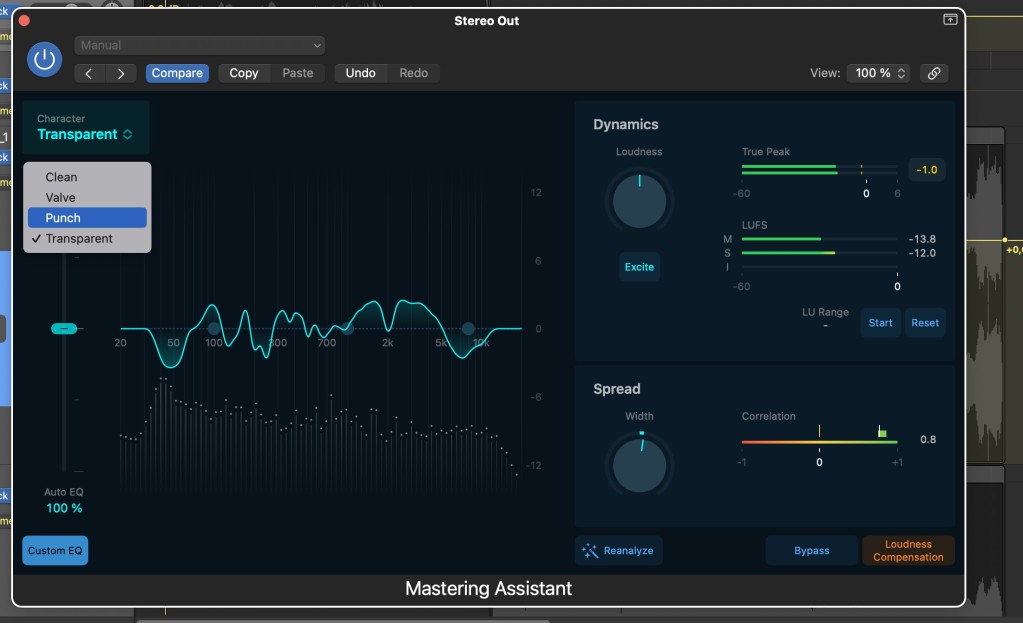

That process is close to the latest version of iZotope Ozone or the just-announced Mastering Assistant in Apple Logic Pro 10.8, so I did side-by-side comparisons with those tools. (The time to analyze the track was also similar, performance-wise, on my M1 Max MacBook Pro – not to say they’re doing the same thing under the hood, but at least from a performance standpoint.)

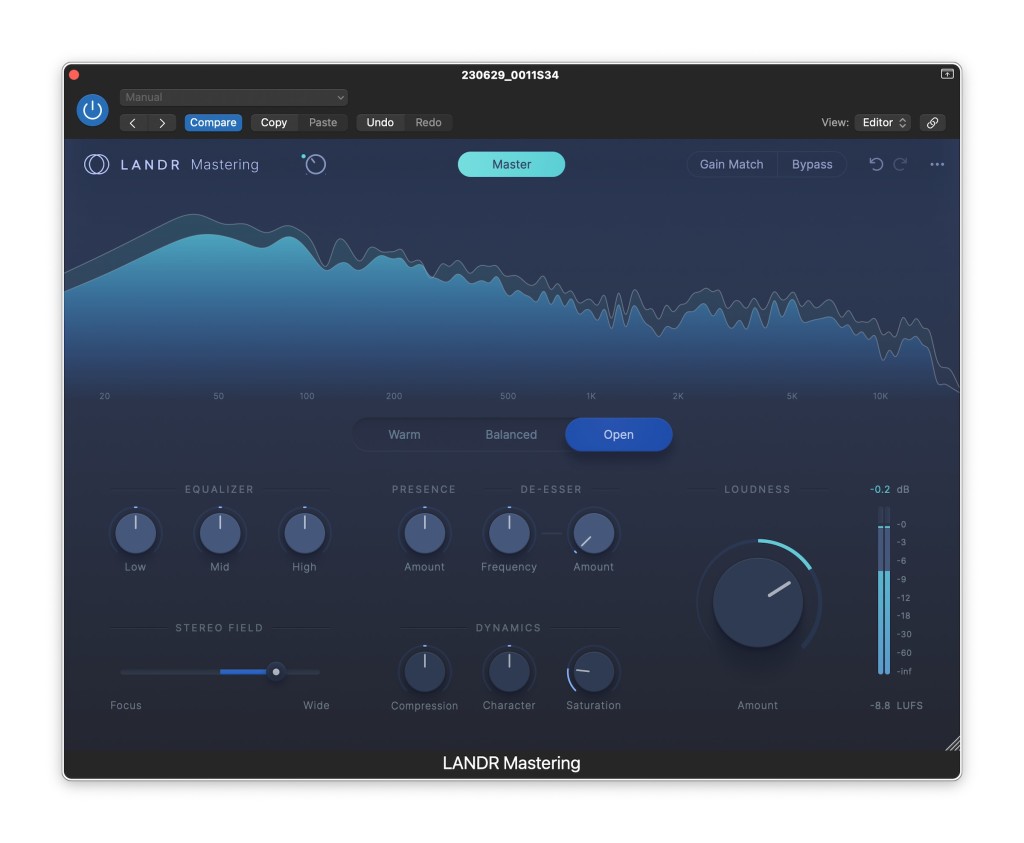

Then you get into the controls:

- Three modes: Warm, Balanced, and Open.

- Loudness, an overall amount (+/-), though resetting this to zero does not mean bypassing dynamic adjustment, which is a little confusing.

- 3-band EQ (high/mid/low).

- Presence ,which impacts the vocal range of the track (though can be useful in instrumentals because our ears are attuned to that range).

- De-Esser with frequency and amount, for sibilance control (on vocals).

- Stereo Field, bipolar, both increasing width and narrowing width (labeled Focus here).

- Dynamics with Compression amount, Character, and Saturation. Compression is an overall amount knob. Character is essentially a combined attack/release timing knob (so turn to the left for punchier results, and to the right for smoother adjustments). Saturation adds a bit of harmonic distortion, modeling analog transistor/tube gear. (I think that’s adjusted based on the mode, but it’s hard to be certain since you can’t solo just this control.)

There’s also a Gain Match switch, which I wish all mastering plug-ins had (even if they might sell fewer licenses). Switch it on, and you hear the original and mastered output at the same volume – an ideal reality check for what you’re doing beyond just turning something up. (Plug-ins with A/B controls, at least, I salute you!)

Subtlety is the order of the day. The saturation and presence controls, for instance, are fairly nuanced even at their extremes. Loudness can certainly turn things up to the extreme, but here’s where the AI seems to kick in – it’s really hard to break a track.

The Warm / Balanced / Open switch does yield different results. Warm is described as a vintage master with “softer highs” and a “thick and smooth sound.” Open is more “modern” and about “punch and presence.” Balanced is not in fact splitting the difference, but rather “focused on balance, clarity, and depth.”

Those descriptions fit the material pretty well. The Balanced mode works in a whole lot of cases, with Warm a close second. Open seemed to be material-specific, but delivered on the added punchiness on materials where you would want some more dynamic input.

I have to think of a flying metaphor here. Think of your conventional mastering tools like a fully-manual, mechanical airplane – which means you can do anything with it you desire, including performing extreme acrobatics and also… crashing into the ground. The LANDR Mastering Plugin is like a fly-by-wire aircraft with autopilot on – you turn the controls to point where you want to go, and it follows. That works well for routine travel, but you will find it harder to paint outside the lines. This is all interesting from a design standpoint, as it’s not hard to envision these kinds of “autopilot” features being incorporated in other plug-ins as an option. Switch on the auto mode when you want it; turn off the safeties when you have some more specific concept.

The LANDR Mastering Plugin is like a fly-by-wire aircraft with autopilot on – you turn the controls to point where you want to go, and it follows.

The UI is lovely and refined, and while early builds seemed to have some glitches with instantiation and analysis, the current build is working well. There’s a useful spectral display and a meter with LUFS. I wish there were more detailed meters, like stereo correlation or the ability to see the master out more clearly, though I’ll just pull up a metering plug-in to check what it’s doing. You also can’t target by LUFS (overall volume) first, which seems like a missed opportunity for machine learning. But it’s nice having all the tools here in one place.

This approach is a lot like what’s in the new Logic, down to the integrated UI. But as with Logic, the restrained interface means you can actually use LANDR with other mastering and metering tools easily – for instance, if you’re mainly focused on a couple of LANDR’s modules and doing other work elsewhere. I didn’t expect to have that become useful in that way, so it was a pleasant surprise.

In use; comparison and conclusions

Look, the main thing is: LANDR’s results now sound really, really good. I threw a bunch of audio at it: experimental music, experimental pop, ambient sounds, techno, hard techno, live sets. It even managed to do something with a rough mic recording I had of a live set at front of house. I broke the rules and applied a second instance of LANDR on the live mic, which miraculously turned a nearly inaudible field recording into something that balanced out with the line level. Result? I was able to mix audience and line input into a convincing sound stage and music.

I could give you examples, but it’s honestly probably better for you to use the free version of the web service and try some of your own material since it is so material-dependent.

I was also surprised that the controls can still give you the ability to listen and get what you want – not just hit “auto” and be done with it. They just get you there more quickly.

LANDR’s results now sound really, really good.

And these can sound a lot like the results you’d get turning over a track to a mastering engineer and studio. I gave my preferred mastering engineer a go at this, too, and they were also impressed that it approximated a lot of their own results – even having told me for years they largely oppose this AI-driven approach. They still understandably preferred their own more tailored approach and broader range of possible results, but maybe that itself is saying something. LANDR represented the most common mastering they’d apply. It’s a shortcut to just those results, not a replacement for the full range of what a human can do.

Apple’s Mastering Assistant is remarkably similar to LANDR now (the Loudness Compensation button is the same as Match Volume, even, and note the character options). It’s included in Logic 10.8, which is compelling – but for automated results, LANDR has the edge for me. (YMMV.)

I also have to say I greatly preferred LANDR Mastering to options from Apple and iZotope. (I’ve asked Apple for comment about what, if any, of their tech uses AI, but I didn’t get a response.) Logic Pro’s Mastering Assistant, to be fair, worked reasonably well – if you’ve got Logic and a Mac (and macOS build) capable of running Logic 10.8, you’ll probably want to start with just that. And I’m happy just to have Apple’s existing tools with a consolidated UI. Apple also has two features I’d love for LANDR to include: there’s a correlation meter, and you get a visual on what EQ curve it’s applied. (It also analyzes the entire track at once.) But I was generally a bit happier with the results and additional controls from LANDR Mastering across the same test material than I was with Apple’s bundled tool. I’m not sure I’d buy LANDR if I had Logic, and of course, you can buy an entire Logic license for roughly the price of LANDR, but it’s still good to know there’s competition.

With iZotope, I had the opposite issue – you get way more control, tools, and UI options than LANDR provides. And I know Ozone is beloved by a lot of folks. I just found a lot of iZotope’s automatic detection settings made stuff sound worse, even to the point of distorting material or suggesting dubious settings – maybe it’s a taste issue, but it seemed over the top. And the UI options gave me too many choices. I tend to just return to my existing tool suite rather than Ozone in that case. LANDR really wins out in a clean UI and strong results. Don’t hate me, NI.

So, for the use case of getting quick automatic results – whether you just need to mock something up before you send a final version off to mastering, or whether you need a tool to get some fast results in addition to your other tools – LANDR fits the bill.

But… and now here are a couple of very significant “buts.”

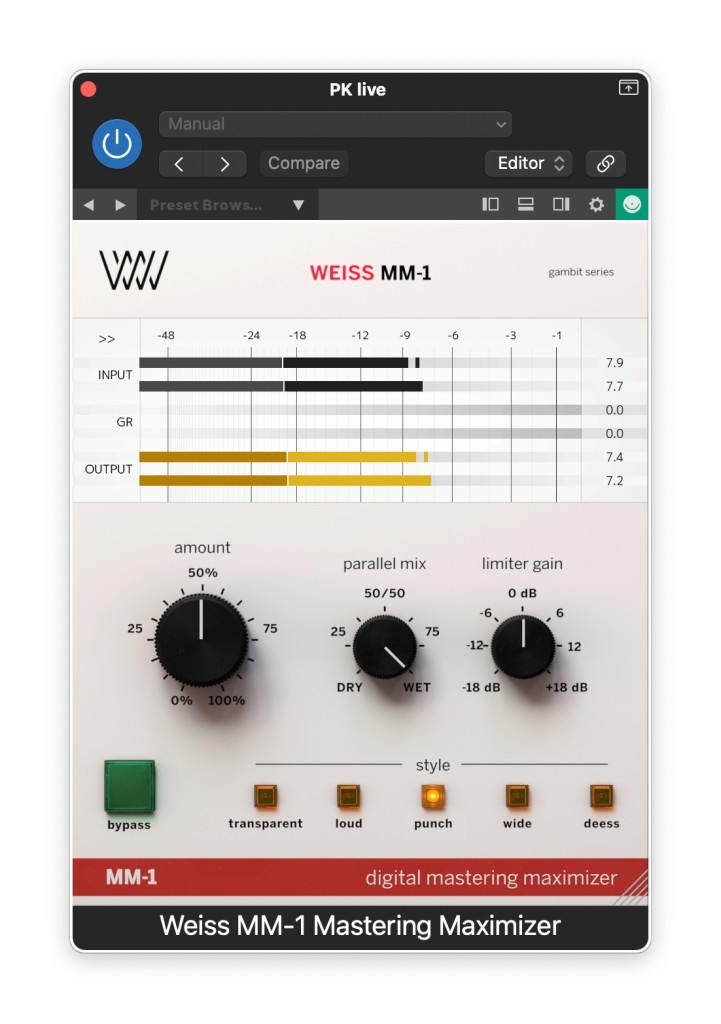

First, one problem with LANDR Mastering is that the other mastering plugins out there are so very good – and let you make more choices. LANDR is fast, but it’s not that hard to get to similar results with your mastering arsenal of choice. I found myself comparing the results to using Softube’s Weiss Mastering Suite, and even wound up in some cases just turning LANDR off and doing the same thing with my own tools.

Hard to use? Not really. Something like Softube’s Weiss Mastering Suite also has a pretty UI and simplified knobs, and remains worth a look even for relative mastering novices.

Second, there’s the price. It’s great having a perpetual license, but LANDR Mastering Plugin is definitely in the price range of other mastering tools. I’m sure some folks will balk. There is a subscription option, and for all the anti-subscription rants in music, it might be worth considering it – just because AI tech in general is moving so fast. A no-commitment monthly subscription isn’t a bad idea.

Honestly, I’d be really happy if LANDR Mastering Plug-in just had some kind of advanced mode – the ability to turn some of that “autopilot” off and adjust more settings manually. You’re restricted even in your ability to bypass modules – turning all the settings to zero doesn’t sound the same as engaging “bypass,” so it’s really all or nothing. LANDR still remains a black box.

As with so many AI breakthroughs at the moment, you do wind up getting a stronger sense of what the human engineers do. LANDR is good at finding a most-likely-case scenario, but when you want to get creative, you’re likely to go back to more precise tools. Ultimately, there are a lot of ways to master a track, and it’s not something that can be reduced to a simple set of knobs. That’s why there are so many mastering plug-ins competing in the first place – and so many engineers. It’s incredibly personal.

If you’ve got the budget for this, though, it’s nice to have in your toolbox. Anyone who’s done photo editing will get it right away. This is the quick color profile, the “magic wand” auto setting. And it has the right balance of controls to still get relatively personal with it, just as you can with image filters – it’s all dependent on the content and input.

Ultimately, there are a lot of ways to master a track, and it’s not something that can be reduced to a simple set of knobs. It’s incredibly personal.

When you have time, you absolutely are going to go manual. When you need to get creative, you will, too. But when you’re pressed for time – and professionals often are – having this is handy, even if just for a quick what-if versus your other options.

LANDR’s product offerings, sale, buying advice

LANDR has a holiday sale on through January 2 which also brings the price point down to a place where I think it’s easier to say yes.

The subscription offering here is pretty generous and comes with a bunch of other goodies to sweeten the deal. I didn’t fully test that subscription, but it’s one of the two or three right now I think might be worth considering for musicians.

All the subscriptions are available as monthly or billed upfront for a year. That is especially economical for a mastering tool, because you can just switch it on when you need it. The “Studio” subscription is web-only, so if the plug-in is desirable, you’ll want to pay for Studio Pro, which also includes unlimited WAV and HDWAV output.

There’s also a distribution option with 100% royalties (not that we need another one), and releases do live forever – so you don’t lose distribution as you cancel, which is how many of those options work. They also include more LANDR effects for instruments and voice, the popular VocAlign plug-in, and a basic version of RePitch, plus high-quality DAW streaming and messenger and community tools for collaboration.

Some really nice effects are in there, too – from Kelvgrand, Cableguys, Arturia, and others.

The perpetual license is also 25% off. See pricing:

https://www.landr.com/pricing/

LANDR Mastering Plugin is available on sale from Plugin Boutique

If you buy something from a CDM link, we may earn a commission.

I’m encouraged. I honestly came into this expecting not to like LANDR much, and I’m impressed. As I said, I resist the “AI keeps getting better and better” as if magical elves are doing the work, because I know a little too much about how it works. But this is the kind of machine learning tool that is showing more promise for actual musicians. Unlike big data “AI” offerings in imaging and text, this tool isn’t just stealing the work we all did on the internet and pooping out generic (or even inaccurate) results. It demonstrates two things. First, it shows you can design tools that use input to map results, rather than just giving you a big menu of presets that may or may not be relevant. Second, it demonstrates ways in which machine learning-powered processing can combine complex groups of parameters into a coherent UI.

In the end, it could even help generate more mastering work. Once you begin to get your ears more used to the results effective mastering can apply, the more you’re likely to want to learn more about EQ, dynamics, and spatial processing – and the more likely you are to realize how important an engineer is to this phase of the process.

I’m glad for all the hype, LANDR has chosen a pricing model that includes subscriptions and permanent licensing and that they’re not undercutting human mastering services. In the end, this won’t be for everyone – you may simply have enough plug-ins already to do the job. But it’s worth trying the web service to see if it’s for you, alongside those other specialized tools. And it’s a model for some of the more nuanced ways machine learning can be used in plug-in design.

So (unpopular opinion) 2023 showed us what AI is really for: slightly better DSP, and making fake LEGO sets. I’m good with that. Now just give me the latter in physical form; mastering with LANDR could give me plenty of time to assemble the Delia Derbyshire Radiophonic Workshop Playset and Stockhausen Helicopter Collection.

More takes (well, you’ll find many more, but I appreciate we get the human comparison in these two):

Also, please, for April Fool’s, someone make a plug-in that’s a cross between the HAL 9000 and Bob Katz that constantly bugs you that you need more dynamic range and ultimately threatens to kill you because you tried to increase the LUFS too much.