The beat tag “It’s Kel-P Vibes!” — cooed sultrily at the start of some of Afrobeats’ best tracks — is a signal you’re in for a good time. Kel-P is the 27-year-old producer from Lagos behind much of Burna Boy’s Grammy-nominated African Giant as well as Wizkid’s “Ginger,” and, as he tells Rolling Stone, upcoming projects from heavyweights like Davido, Wande Coal, and Adekunle Gold.

Kel-P is among a budding crop of Nigerian producers (including Pheelz and Young John) hopping up from behind the boards and pursuing careers as the lead act, too. Kel-P dropped his first EP as a vocalist, Bully Season Vol.1, last month, full of tropical odes to women, meant to get them on the dancefloor. “I’ve always wanted to be an artist. The question is what made me start producing,” Kel-P says over Zoom.

It happened almost by chance. In 2017, Sarz, the producer of the recent hit “Mona Lisa,” took Kel-P under his wing. They met when Kel-P came to his studio as a part of a seven-person music group — in which he sang. When Sarz relayed to them that at least one of them should make the beats they performed on, Kel-P took on the task and found something he excelled at. He told Nigeria’s The Guardian that he was one of his ensemble’s worst vocalists. “I fell in love with the craft as a producer because I felt like I was ahead of my group this time around,” he says on our call.

Now, Kel-P is bridging his longtime passion for performance and his newer skillset as a beatsmith at a high level. He’s on Zoom from Houston, where he’s working with a music director to fine-tune the live performances he plans to kick off at festivals in April. He appears on the new Creed III soundtrack, executive produced by J. Cole’s Dreamville, as both an artist and a producer. “If I don’t come with the right song, the world is going to [say], ‘I think Kel-P should keep producing. This singing thing’s not for him,” he says. But instead, he finds that he’s able to pull people in as an artist too. “And when they go find out who I am, and they’re like, ‘Oh, so he made all these records for all these guys in the past!’ That’s how I wanted it to be. I was looking for that huge surprise factor.”

Editor’s picks

Kel-P talked to Rolling Stone about his path, techniques, and new sound.

So, when you became Sarz’s apprentice, essentially, what was your process of learning how to produce like?

I started using Fruity Loops [now known as FL Studio], and I was watching. All he showed me was the basics. When I learned the basics, every time he’s working with artists, if I don’t understand something, I’m always asking questions. I’m always in front of him, staring at the computer every time he’s working. And I was always practicing. He was always telling us, “do this,” ‘Do that,” “Come back, play our beats for [him]” and all of that. I was not the only one he was coaching. We were four or five in numbers.

After 2018, I decided to find my way. I’m like, “You know what? I know a few things, but the rest of the things I don’t know, Sarz is not going to teach me. All this kind of thing is practice. I just have to keep practicing and watching a couple of videos on YouTube and stuff like that.” So I learned everything so quick in the process. I’m a very fast learner.

One of the things that I like most about your production is that it’s so textured. It almost sounds like you could get a band of people together and tell them what to play. Did you play any instruments before you started learning how to produce at all?

Just the piano, but it’s not like I play, play. I just have an idea. The truth is, I don’t even like to play an instrument because playing an instrument as a producer, for me, it just pushes you in one box of trying to just play simple chords. Yeah, simplicity is good, but I like to play [chords] using my software because it pushes me harder to try different notes, try different things because it’s computerized. It’s not live, where you can just play whatever comes to your head — how you feel. With the software, you have to keep trying things, and you work with your ears. So I was always working with my ears.

Related

When I’m making records for artists, I picture them in my head, how they’d perform the record on stage. It’s like I’m making the record now, and I can see Burna Boy performing on stage. So I try to make the beat different so that the stage fans can feel it.

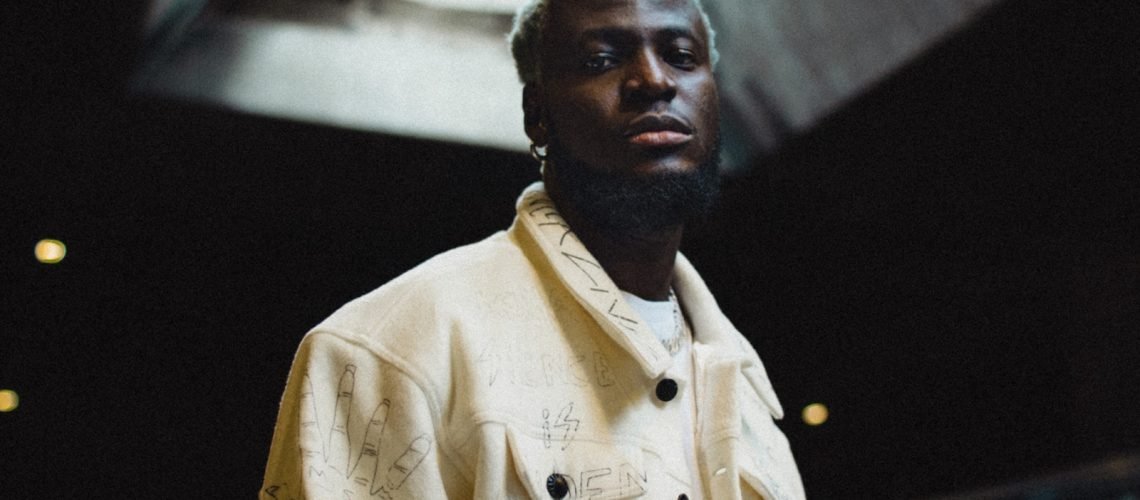

Kel-P

Virgin Records France

How did you and Burna Boy get together?

It was just a phone call. I just got a phone call from a friend of mine that worked with before, and when I picked the call, it was Burna Boy talking. I thought he was the one because Burna Boy used his phone.

He was in the studio with Burna Boy, and Burna Boy had recorded on one of my beats and was asking him, “Who made this? Who’s the producer? I want to see the guy who made this beat.”

He decided to call me. When I picked the call, I’m like, “Yo, bro, what’s good?” And the next thing I heard on the phone: “Oh, this is Burna Boy. Where are you?” I’m like, and I said, “Burna Boy Ye?” Said, “Ye.” And then he said, “Yeah, pull up to so-and-so place.”

That was like 6:00 AM in the morning. I think they went to club, and after the club, they went to the studio. I went straight to the address where he was. We went straight to a hotel, and in two weeks, we made 13 songs. In two months, we made 33 songs. We just have a few out, and the rest of them are on my hard drive. I met him in August, and by September 2018, the next month, we already dropped the first song, “Gbona.”

I never knew I was even making an album for Burna Boy. I just thought he was doing a production camp in the hotel, and there were a lot of producers. It was a lot of producers coming back and forth, but I did not leave the hotel. I was there. I did not go back home. I went back home two months after.

Still, you’ve always wanted to be an artist. You learned to produce by happenstance. What made this the right time for you to drop your own music?

I was supposed to drop a project way earlier, in 2020. But that was a producer project, the kind of thing where a producer features a lot of artists. back and forth things happened on the business side, ups and downs. That whole situation made me…I told myself, “You know what? I can do this thing myself. Let me travel to different countries, tapping the producers. Go look for my sound as an artist and figure it out.”

When I did all of that, it was just something I felt — “Okay, I guess it’s the right time to put a face behind the name Kel-P.”

When you went looking for your own sound, what did you find? What do you think that it’s shaping up to be?

“One More Night” is a mixture of Afrobeats, R&B, and Dancehall. When I found my own sound, the first thing I asked myself was, “Okay, what would I call [it]? Because I know people are going to ask me these questions in so many times.” I told myself I’m just going to call my own sound Afro-Dancehall because every one of my songs has [that] influence.

The cool thing about “One More Night” is that it samples Nelly and Kelly Rowland’s “Dilemma” without being overly reliant on the nostalgia to hit. It still feels very new and personal. Was that a goal?

I was just somewhere where I went to get food, and they played the record [“Dilemma”] randomly, and the record just hit me. I knew that record, of course. I grew up when the record was popping. I was a kid. Shout out to KDAGREAT. When I hit him up, and I told him, “Bro, we need to sample [“Dilemma”], he sent me a bit in two days with the sample in it. I’m like, “This is too perfect.” I heard the bit and went straight to the studio. We worked on a few things, went back and forth, and changed a few things. My whole idea when I was recording the song was just to make women dance.

I decide to attack the beat with such a cadence that is spacious at the beginning, and a universal melody, universal chorus, universal hook that this song can penetrate in London, in America, in Germany, or whatever.

I decided to approach the record that way, and when I recorded the song, I recorded the song from top to bottom, just melodies. There was no lyrics in it. Then I think I FaceTimed a couple of my female friends, five of them. And I played it to them, and they heard it. They’re like, “Oh, this is fire.” The creative process of that song was not hard. It was quite easy because that’s what we do, bro. The only thing that was heard about that song is just clearing the sample.

When did you make the song? How long ago?

I made the song two years ago. was, I told myself, “I want to be ahead of my time.” I want to make records two years back, three years back, and I hear it two years after the world is going to believe that I made that song yesterday, because it sounds fresh. I respect myself on that level, because I’m like, “Nobody has been able to create something like that for the past two years.” Every time anybody that drops an album within that whole two years, I go listen to the album from top to bottom. If I find a single element that sounds like my song, I go back to my drawing board and I change a few things.

When you say anybody, are you looking particularly at African or dancehall artists?

No, anybody worldwide.

And last thing before we get off, how did you name your EP?

Bully Season, actually, it was one of my managers that came up with the name one day. I made a record for Skip Marley, and they posted on my page because they handle my Instagram. [For] the caption, they wrote something, blah, blah, blah, “Da Bully.” And a friend of mine from Jamaica, a producer, text me on WhatsApp and said, “Da Bully. I love that name.”

Trending

Then I told my manager who posted that on my page, “Okay bro, keep using the Da Bully thing. It’s making sense,” basically, [because of] everything I’ve passed through in my career, my life, my work ethic. Like I said earlier on, I was supposed to drop a project in 2020, but because of the back and forth, I just woke up one day and said, “Fuck this, I’m doing my shit.”

I just felt like God really wanted me to do this, and I just felt like God is actually going to be pissed off if He gave me this talent and I’m not using it right. I’ve been hiding myself all the time. I don’t even go for no interviews. I don’t even do no pictures. I only post myself working in the studio. I don’t post myself doing any other thing at all. I don’t show people nothing. I only show them the music. I’ve been hiding because I was working on myself, the confidence, developing myself.