Science and animation are tied together like a moon to a planet. While they exist on distant planes and their connection is invisible, to animate is to have a fundamental understanding of science and movement. The job of both an animator and a scientist is to understand the building blocks of reality; the former bears the burden of twisting and subverting that understanding into a form of heightened reality, a surrealism giving birth to cinema.

Achieving great animation is not fulfilled by a flat depiction of reality but by injecting it with a factor of fantasy in the name of entertainment. Such balance between the believable and the fantastical is what allows Finding Nemo to maintain its status as a classic of the medium. The push and pull between realism and creativity was an internal tug of war for every animator, writer, and visual artist under Andrew Stanton’s directorial eye.

Character animator Gini Cruz Santos and director of photography Sharon Calahan were made familiar with the microscopic details of marine movement and caustic lighting. Their attention to detail helped construct a film whose ocean world and thrilling story hold up 20 years later, despite being developed close to the birth of entirely CG cinema.

The ambition of Finding Nemo was to cross the boundary between land and ocean for the first time in Pixar’s studio history.

“It was exciting and a huge challenge because nobody had ever done anything like that before,” Calahan tells Rolling Stone. “We had no idea how we were going to do it. That’s always kind of a thrill and a little bit panic-inducing, but I knew it’d be something really unique and magical.”

Santos saw the film as an opportunity to improve her skills as an animator. “If you think about it, a fish really doesn’t have limbs. It’s just a big face on a very simple-shaped body,” she explains. “At that stage in my animation career, I knew I could improve on my facial acting.”

Editor’s picks

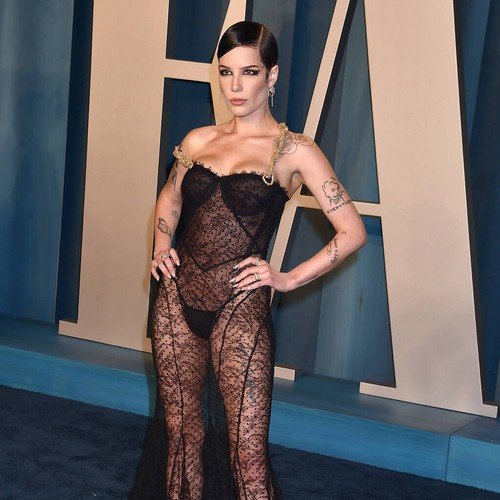

David Newman leads the New York Philharmonic in ‘Pixar in Concert’ at Avery Fisher Hall on May 1, 2014.

Hiroyuki Ito/Getty

Scientific obsession with the ocean was a prerequisite for anyone working on Finding Nemo. Pixar arranged for an ichthyologist (a fish-focused zoologist), to give regular lectures to the staff who also embarked on snorkelling trips to literally immerse themselves in the world they were tasked with depicting. Hiring an expert to the relevant field became a Pixar tradition, as the studio would go on to tackle stories centering dinosaurs and skeletons. For Santos it is not always about taking in the intricacies of scientific detail, as “to hear some of the experts come in and show passion just while talking about the animal is so inspiring for us.” She adds that the team learned specific factoids which animators would have to focus on, like “the motion of the fish, the bones and the structure of the body and why the body does certain things to propel itself through the water, or why the fins will react in a certain way.”

Also presenting physics-based quagmires unique to an underwater adventure is the ability for a fish to move in any direction through water, a far more dense medium than air. Another aid to the animation team was a huge aquarium set up in the animation department, providing easy access for animators to study movement.

Close inspection and repeated test animation was key to Santos cracking the code on realistic movement. “With a bipedal or quadruped walk, the legs are what informs us on how it works in gravity. A fish has nothing. You can put it in a 3D space and just move it around,” says Santos. “So, how do we make it feel like there’s something around the body that has a force that the fish is pushing against? Not only are we making them swim, but eventually we’re going to make them stop and then do gestures.”

Computers at the time lacking the ability to render realistic water physics on their own also presented challenges for Calahan. Visually, Finding Nemo is a journey from the purest, cleanest underwater environments through increasingly murky and waste-ridden seas and back out the other side.

Related

In order to communicate a differentiation in murkiness, Calahan had to stitch together a believable environment. “We had to kind of fake everything. We had to really figure out what made it feel like you were underwater and then develop some kind of control over it,” she explains. “We banged on it for a good year, and then finally, in desperation, we came up with a scheme where we took a bunch of spheres, and just had them moving around, giving them a little bit of form, and then just blurring them to extreme levels to get it to look kind of foggy. Then it became about how to get the fish to swim through the spheres that we have laid.”

Vital to the visuals of Finding Nemo and the film’s consistently vibrant environments was Calahan’s study of caustic effects — the patterns of light that dance on the ocean floor due to the surface’s refraction of sunlight. Sea life exists in an environment of constant motion from sunlight, another difference between the settings of past Pixar films and Nemo. Creative embellishment on scientific accuracy was required by Calahan to make the film palatable and coherent for audiences.

“The caustic light beams gave life to it. You felt like you were in a living, moving environment, so it was important to have that constant motion,” Cahalan highlights. “But yeah, sometimes if the water surface got too busy, we’d have to calm that down. We had to change what would be real because it was too much. We started with reality and then just backed it down.”

Layering creative embellishments over a stitched-together reality was also a tug of war in the animation department. Prior to Finding Nemo, Pixar’s CGI software was incapable of simulating the movement of a fish, meaning specialized development was needed for the film. The software needed to apply an oscillation and swaying to the fish while they were idle, while also allowing for some creative freedom for the animators. In order to ratchet up tension or provide stillness in more emotional scenes, the rules of how something moves through, or is pushed by, water needed to be broken.

Further laws of physics fall by the wayside when incorporating a voice actor’s performance into the animation. Already, the fish model needs to be altered to emphasize the depth of their eyes and the movement of eyebrows (given to the fish specifically for this film), the keys to anthropomorphising any creature used in any Pixar movie. Factoring in a vocal performance means giving the model personality and mannerisms that match the performer.

Santos spent her days tweaking the motions of Finding Nemo’s most iconic invention, Dory. Ellen DeGeneres’ delivery of lines like, “Just keep swimming,” are burnt into the minds of people of a certain age, but it was up to Santos to give those words form.

“When we knew she was going to be in the film, she happened to have a show in San Francisco, and a small team of animators along with the director went to see her because we always like to reference the actor,” Santos details. “It was nice to see her live with her body gestures and what her face was doing when she talked about something because there was already a built-in humor to the texture of it.”

For fans and animators alike, the attachment to Dory has survived two decades. “With all the characters I’ve worked on, I have to say, Dory is really still in my top five characters,” offers Santos. “She is so endearing. The forgetful part of her personality is always fun to watch and still funny to this day. Ellen did a great job with that.”

Making Finding Nemo today, with 20 years of technological progress and advancements in animation software, would have been a vastly different experience. The invention of a volume renderer, a piece of software which has built-in water physics, was key. Calahan emphasizes the modern tools that were at the disposal for the team working on Nemo’s sequel, Finding Dory. “If we’d made it today, we would be using a volume renderer for everything. We wouldn’t be trying to fake caustic light beams. You’d be getting them generated from the water surface,” says Calahan. “For better or for worse, you can get much more realistic effects. In Finding Dory, those effects look a lot more realistic, because it’s actually doing what it should be doing. So to know how it would be different today, I’d watch that movie.”

For Santos, the limitations of 2003 technology was a blessing in disguise. “There’s a practice among us as animators where there’s a restraint that we want to have in our animation,” she says. “One thing that computers brought is that we can move everything and anything all the time, and you don’t really want to do that. Sometimes the hardest thing when we’re animating is not animating. You need the quiet moments.”

The push and pull between what one is capable of doing and what they should do is key to Santos’ philosophy as an animator.

Trending

“We know we can do a lot with technology, but as actors and performers in our craft of animation, when it comes down to animating this one moment, there’s a rhythm to it. There’s a quiet, and there’s also a moment where you want it to be loud,” she shares. “One of the things we always try to teach is how you can do more with less. That’s always a balance we try to find, even if technology allows us to do anything.”

CGI aquatic adventures after Nemo, such as Aquaman and Avatar: The Way of Water, owe a great deal to Pixar’s effort and their endeavor to prove that something like this is even possible. Even then, Finding Nemo is more than a tech demo. The visuals of this film, though stitched together by blurry spheres and non-existent water, are worthy of basking in to this day.