Crises are a given; resilience is a given – to slightly bastardize the author’s words on Beirut’s Underground Scene, Hajar Ibrahim’s portrait of a musical world. But in this book, released this summer, what you get is more personal. It’s the underground telling its own story, rather than having one framed for it.

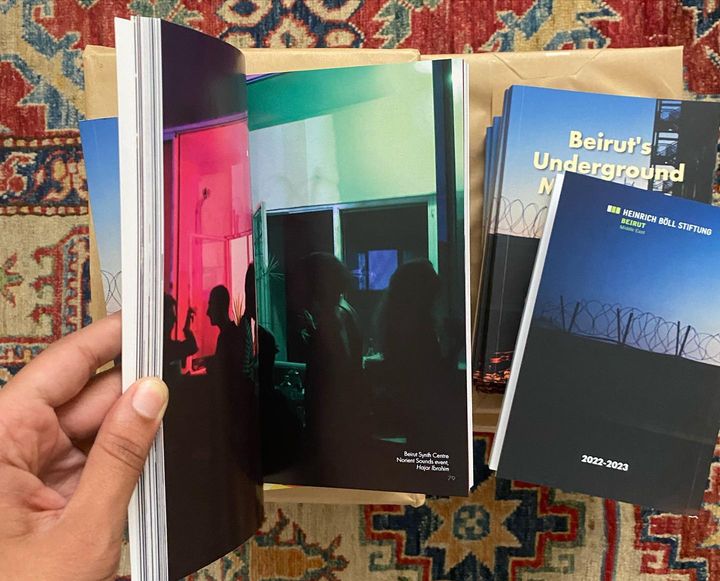

Even speaking as a writer here, it’s strange how often the journalistic picture can seem warped, unfamiliar. Hajar’s book is nothing like that; it’s filled with images and texts from the decades of Beirut’s current experimental realm that feel like a carefully composed scrapbook. The title wisely doesn’t try to be comprehensive or overly structured, but – instead it’s like someone has arranged a week of well-chosen coffees. You get artists who can speak to Beirut’s overflowing love of music. It’s edited but unedited. And crucially I think it will resonate with other underground communities around the world, and their own challenges.

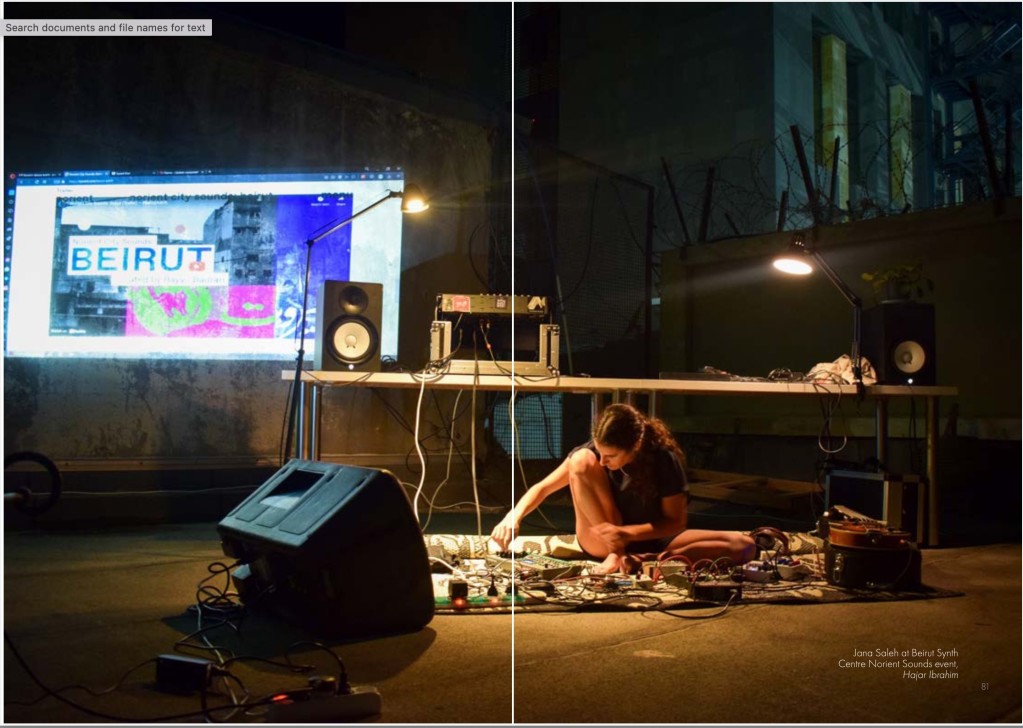

In the spotlight, there are luminaries like Zeid Hamdan, the crew of Tunefork Studios, Marc Codsi, Sandy Chamoun, Ziad Moukarzel (who carries the banner for the Beirut Synthesizer Centre, though Ziad does a lot more than that), Tanjaret Daghet, and Issam Hajj Ali, among others. That provides a decent taste of some of bedrock prolific artists who make up this tight-knit community – at least enough to make you want to go dig up many more. It also finds threads of diaspora and return, of musical answers to crises and lack of space, COVID and explosion and currency catastrophe, and projects like Beirut Open Stage and Lebanese Underground, from rooftops to the sea.

Then the book turns to the club realm – after a stopover at Chico Records, Beirut’s oldest surviving record shop, est. 1964. (Fairouz’ son Ziad Rahbani co-founds Zida Records with Katchik, and the rest is history.) For the club side, you’re treated to 90s rave history, events in the mountains. DJs Ronin and Rea check in from FLOAT, along with 3LIAS.

I feel honestly privileged that some of this feels familiar to me, even, just with my couple of visits and following the music for some years. But I think that’s also a testament to the Beirutis’ commitment to sharing what they’re doing.

The book’s overall timeline covers post-civil war onto the 2000s and recent years, and even some reference to pre-war epochs. An insight into Lebanese club culture missed by a lot of more recent media is surely B018, operating through war … and then another invasion. (If that makes you curious beyond the two-page spread it gets, this is a guidebook also to other reading and research – see this story in VICE, albeit with an unfortunate Berlin comparison in the headline.)

But you get a current perspective, and a sense of the emotional essence of this scene – without any of the sort of exoticization that international press (cough) might bring. I always thought the worst part of this is romanticizing strife, typically from more privileged environs. There’s the horrifying concept that pressures make for a better music scene; it’s like adding delusion to disaster fetish. On the contrary, there’s so much pain around that topic in Beirut – for some having it become too difficult to stay, for some too difficult not to return, and sometimes both at once. No one should be creating any fantasies around that kind of pain, even if it’s been channeled into endurance.

I think reading these stories, you’ll instead get a chance to listen to people talk about these conflicts themselves, and also a sense of love.

“People can’t live without music here,” muses Mayssa Jallad. “It keeps them going … Have you ever been to a Lebanese wedding? People are crazy. They love life.”

And answering my criticism of the foreign gaze, the book concludes with a demand, or maybe even an accusation. “We do not speak of resilience here, we speak for the right to live a free life where you are not applauded for surviving death.”

Here’s to that right.

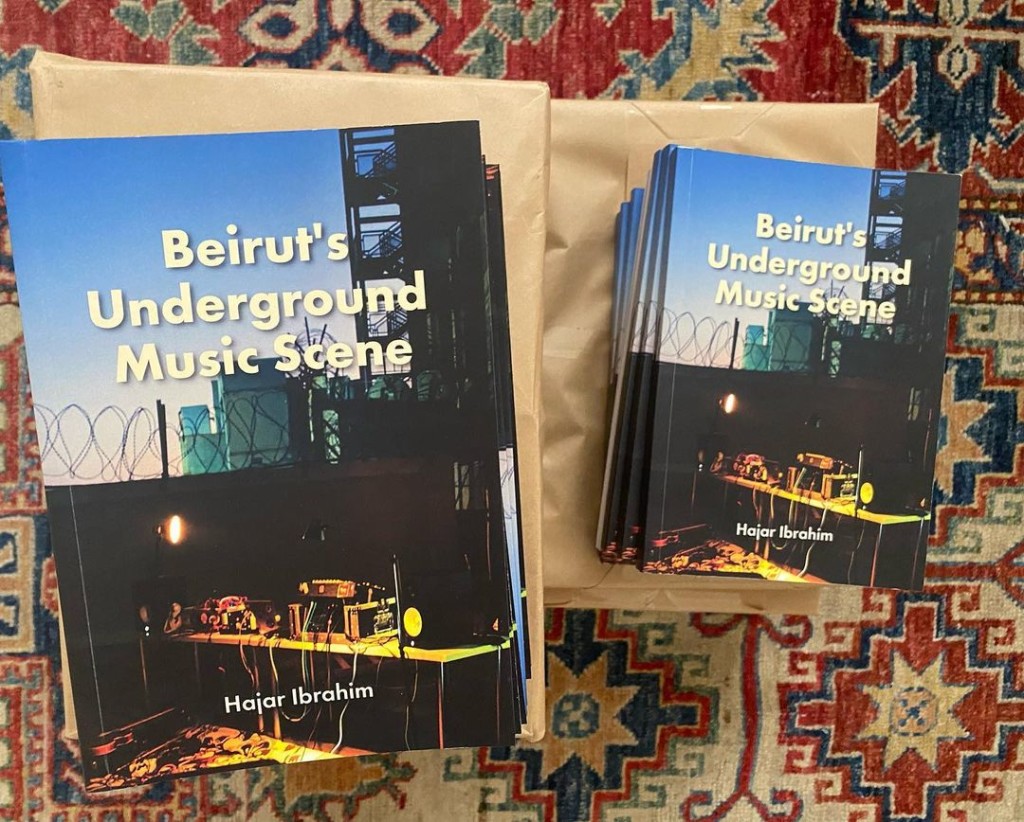

Print versions are available in limited supply; a PDF is available for free download.

Beirut’s Underground Music Scene. Heinich Boell Foundation:2023.

Here’s the author’s announcement. (Embedding is broken for me at the moment for some reason.)